From 1624 to 1662, the island of Formosa – present-day Taiwan – was under the rule of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) (fig. 1). Prior to this period, the trade in Chinese porcelain proved challenging, as the VOC had no direct access to China and supply was therefore unstable. From Fort Zeelandia, the trading post established by the VOC on Formosa, the porcelain trade proceeded far more smoothly. For several consecutive years, more than 200.000 pieces of porcelain were exported annually to the Dutch Republic, representing a more than twofold increase compared to the preceding period. During the occupation of Formosa, the VOC exercised more direct control over the supply of Chinese porcelain. This period, however, was short-lived: in 1644, the Ming dynasty in China collapsed, leading to a rapid decline in porcelain production, and the VOC was subsequently expelled from the island by Ming loyalists who had taken refuge there. From the perspective of the porcelain trade, this article sets out how the Dutch ended up at Formosa and how they fared there during this period.

VOC trade from Formosa to China

In short, the colonisation of Formosa stemmed from the VOC’s strong ambition to establish a direct trading link with China. Even before the Dutch sailed to East Asia under their own flag, expectations of China and the level of its civilisation were high. In early Dutch travel accounts, China was portrayed as a wealthy and culturally sophisticated country. Porcelain – a product of distinctly Chinese manufacture – came to symbolise this image. Compared with European earthenware and stoneware, the material was of unprecedented quality, both technically and aesthetically: it was crystal white – hard, smooth and lustrous, yet at the same time almost translucent. Moreover, Europeans had no idea what this type of ceramic was made of, which only added to its fascination.

It proved, however, difficult to establish a system of free trade with China. The Chinese empire was a great power in East Asia and functioned as the dominant cultural sphere of influence, but this went hand in hand with an isolationist policy: foreign merchants were generally prohibited from settling on the Chinese mainland to conduct trade. The Portuguese, however, had succeeded in establishing a trading post in Macao, and the Spaniards enjoyed indirect access to the Chinese market via the Philippines. In the early seventeenth century, the Dutch made several attempts to gain a foothold in Macao, but to no avail: negotiations repeatedly broke down or escalated into conflict with the Portuguese and the Chinese.

The porcelain trade was not the VOC’s foremost priority. The spice trade was far more lucrative, and it was on the Spice Islands – the Moluccas in present-day Indonesia – that the company initially focused its efforts. Consequently, a direct trading relationship with China failed to materialise in the early years. Nevertheless, through intermediary trade and by privateering Portuguese and Spanish vessels, the Dutch were still able to acquire porcelain and other Chinese luxury goods. Chinese silk, as well as porcelain, were key commodities for the VOC within the intra-Asian trade networks with Japan and India, generating substantial profits.

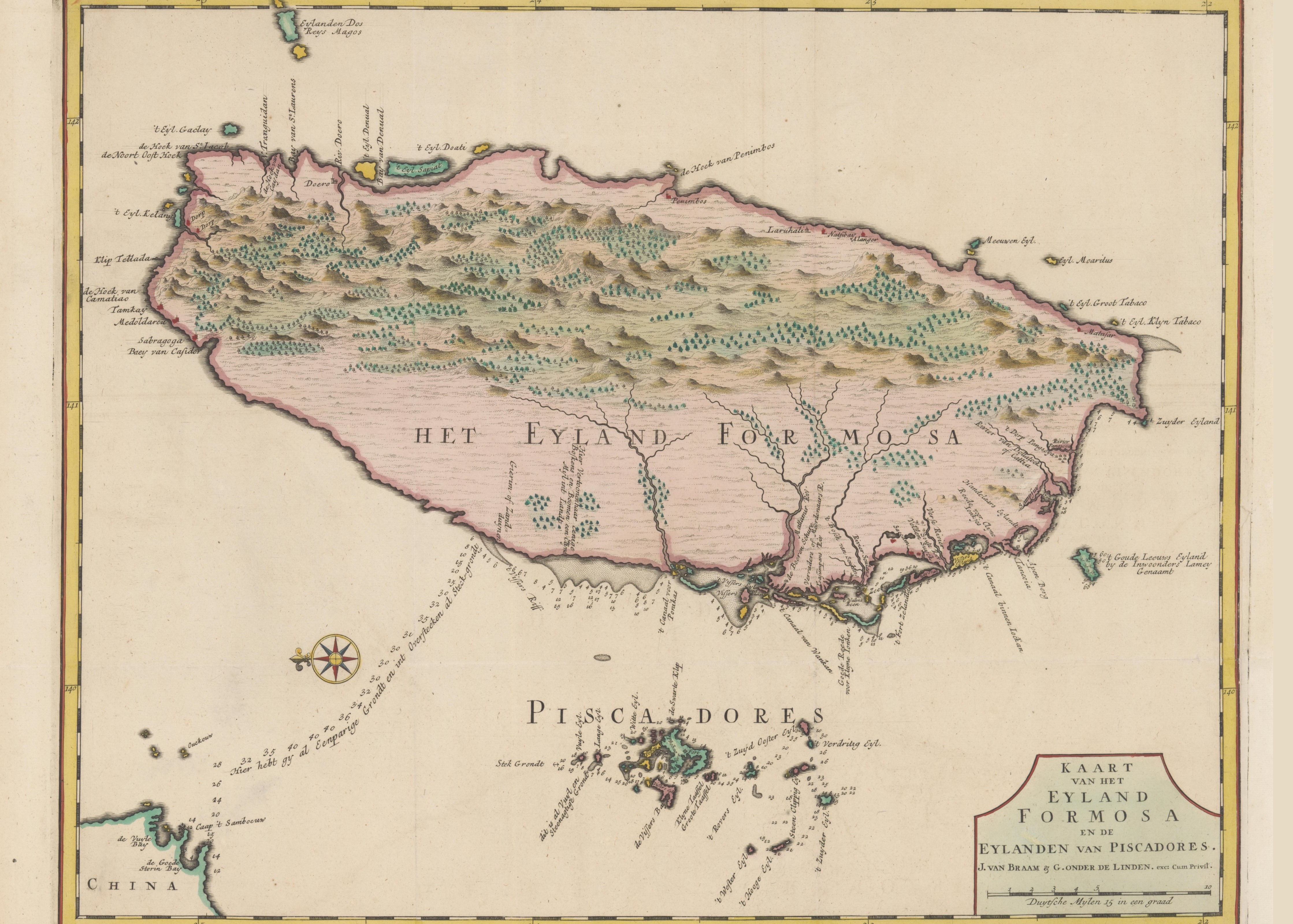

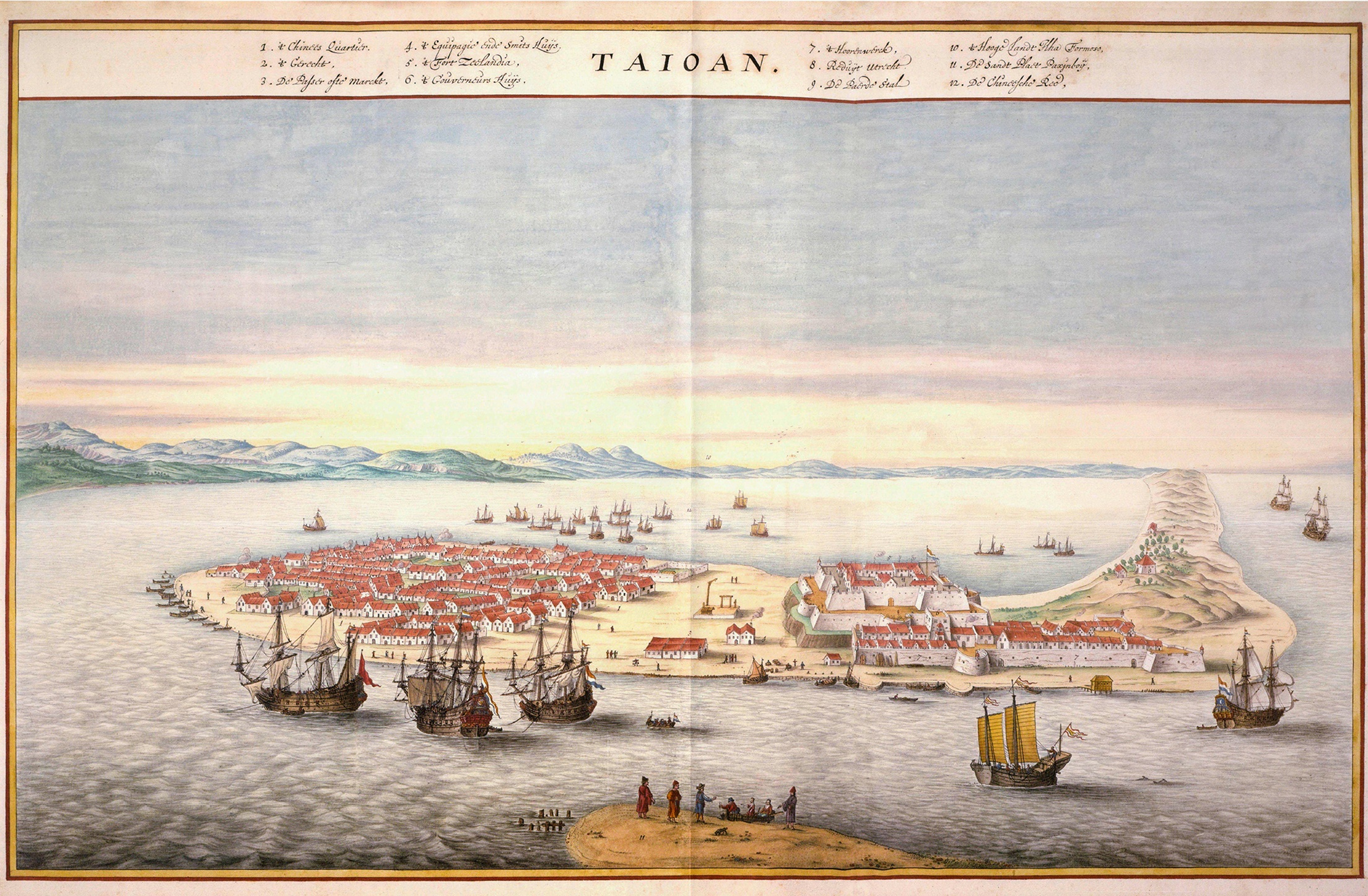

A steady supply of Chinese luxury goods was therefore still highly desirable. In 1622, a plan devised by Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629), then Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, led the VOC to an attack on Macao. This assault failed, after which the Dutch shifted their attention to the Pescadores, a small archipelago off the east coast of China, opposite the province of Fujian. There they established a fort in the hope to reopen contact with China. This move, however, was viewed as a provocation by the Chinese empire. After two years of intermittent skirmishes an agreement was reached: the VOC was required to withdraw from the Pescadores, but in return was permitted to establish a fort on a nearby island, known to Europeans as Formosa. Accordingly, the Dutch occupied the sandbank of Tayouan on the south-west coast of the island – today the Anping District of Tainan – where they built Fort Oranje, in 1627 renamed Fort Zeelandia (figs. 2–3).

The VOC’s principal aim in establishing a trading post on Formosa was to generate profit through intermediary trade with China. When the Dutch arrived, the island had already been inhabited for centuries by a wide variety of Indigenous groups, some of whom were regularly engaged in warfare. This complicated the VOC’s efforts to exploit the island and its commercial resources – such as deer hides – to their full advantage. For this reason, the VOC decided to pursue the pacification of the local population, in which missionary activity played an important role. The enforcement of ‘peace’ was frequently fraught with difficulties, and in the face of resistance the company at times resorted to excessive violence. Migration of Chinese settlers to the island was also actively encouraged, including tax collectors and farmers who cultivated sugar cane and rice. As a dominant minority, however, the VOC’s hold on power during its rule over Formosa remained precarious.

The porcelain trade via Formosa

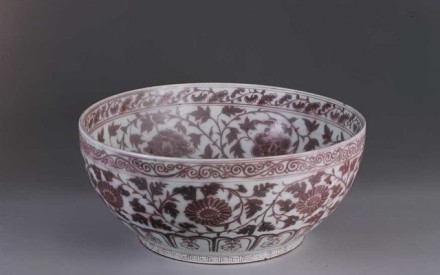

Until the early 1630s, the porcelain trade with China via Fort Zeelandia progressed only with difficulty. The Chinese authorities were still unwilling to engage in trade with the Dutch, and the Chinese coast was moreover plagued by piracy. The VOC attempted to initiate free trade through several prominent Chinese merchants. In China, merchants traditionally occupied the lowest rankings of the social hierarchy and operated in a semi-clandestine capacity. This worked to the VOC’s advantage, as it was easier to establish contact with them than with the official Chinese authorities. Even so, only occasionally Chinese junks came to Formosa to conduct trade. During this early phase of the VOC’s presence on the island, commerce centred mainly on so-called kraak porcelain, such as dishes, cameelkoppen and clapmutsen (fig. 4-6). The majority of this porcelain, however, was not obtained via Formosa, but through intermediary trade and privateering.

This challenging initial phase came to an end when an important Chinese intermediary of the VOC – Iquan (1604–1661; Chinese name: Zheng Zhilong) – was appointed to an official position within the Ming administration. In cooperation with the VOC, Iquan put an end to piracy along the Chinese coast, clearing the way for free trade. In 1633, a trade agreement was concluded, promising that each year five large and eight smaller junks would sail between the port cities of Fujian province and Fort Zeelandia. Thanks to these arrangements, the porcelain trade flourished for a period of approximately ten years. This enabled the VOC to exert a degree of control over the types of porcelain produced in China. By letter, the Heeren XVII in Amsterdam could indicate their preferences, which were conveyed in writing via Batavia to Formosa. Based on these accompanying examples, porcelain in Western shapes was produced in China for the VOC. A beer tankard from the collection of the Groninger Museum and a large dish from the collection of the Princessehof Ceramics Museum provide representative examples (fig. 7-8). The cone at the centre of the dish supported the foot of a – now missing – ewer.

Until 1640, the Dutch could rely on a stable supply of porcelain. These peak years came to an end when in 1644 the Manchus seized power in China and established the Qing dynasty, which resulted in the fall of the Ming dynasty. Prolonged social unrest had already prevailed, culminating in civil war and famine. Many Chinese labourers, including those employed in the porcelain industry, lost their lives. The civil war in China ultimately also led to the Dutch having to give up their colony on Formosa. A group of Ming loyalists, led by the military commander Coxinga (1624–1662; Chinese name: Zheng Chenggong, the son of Iquan), fled from Fujian to Formosa and in 1662 captured the island from the VOC. As a result, the porcelain trade with China came almost to a standstill. To meet the continuing demand for porcelain in the Dutch Republic, the VOC began placing orders in Japan. The shortfall was also partly offset by the trade in Persian faience and Delftware. Stability returned to the Chinese empire under the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1662-1722), and the production and trade of porcelain for the export market – including for the Netherlands – were resumed at full pace.

All in all, the colonisation of Formosa constituted a unique period in the (porcelain) history of the VOC. Not only did it mark the first time that the company was able to trade directly with the Chinese empire, but the occupation of the island also represented the VOC’s first instance of territorial colonisation in Asia. The remnants of the Dutch presence in present-day Taiwan remain visible today, notably in the ruins of Fort Zeelandia and in the urban layout of the Anping district.

Literatuur

Van Amstel, Aad, Barbaren Rebellen en Mandarijnen: De VOC in De Slag Met China in De Gouden Eeuw, Amsterdam: Thoeris, 2011.

Van Campen, Jan, Eliëns, Titus (Eds), Chinese and Japanese Porcelain for the Dutch Golden Age, Zwolle: Waanders Publishers, 2014.

Finlay, Robert, The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History, The California World History Library, 11. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Parthesius, Robert, Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

Ketel, Christine, Dutch Demand for Porcelain: The Maritime Distribution of Chinese Ceramics and the Dutch East India Company (VOC), First Half of the 17th Century, Leiden: doctoral thesis Leiden University, 2021.

Blussé, Leonard, ‘Van tussenpersonen, tolken en trotse heersers.’ Aan De Overkant: Ontmoetingen in Dienst Van De Voc En Wic (1600-1800), Ed. Wagenaar, L. (Lodewijk), Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2015: 11-33.