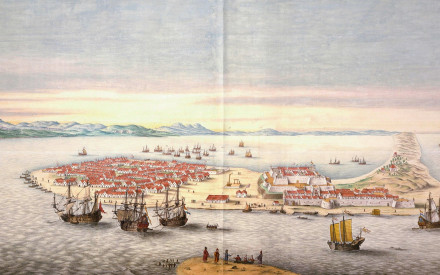

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie - VOC) was established with aim to buy pepper and spices in Asian regions. In most European countries, porcelain was a scarce and luxury item at the beginning of the seventeenth century, but rapidly became very much in demand, and good profits could be made at auctions. Gradually return shipments with commodities from Asia included Chinese porcelain. At first the VOC directors did not send any specific orders for porcelain and merchants bought what they could find at the trade posts of Patani on the east coast of the Malay Peninsula, and Bantam at the tip of northern Java, Indonesia.

It is estimated that about three million pieces of porcelain were sent to Holland between 1604-1657. From 1615, the directors of the VOC ordered shapes that had not previously been requested, such as bottles and ‘nice flowerpots’. A new instruction was included: the decoration should preferably be ‘not completely white but everything [with] blue [decoration]’ (geen wit maer alle geschildert blaew werck). Between 1634 to around 1644, (the end of the Ming dynasty), shipments of commodities (mostly sugar and ceramics) were regularly transported by Chinese junks from Fuzhou and Xiamen to Fort Zeelandia on Formosa (Taiwan). The amount of Chinese ceramics purchased by the VOC was then at its height. For example, we see that in 1638, the storage stock at Fort Zeelandia was 890,328 pieces. Cargoes were first transported to Batavia where they were re-loaded onto the return ships to the Netherlands or even sailed directly to the Middle Eastern ports of Mocha and Gamron with specially ordered porcelain for those markets.1 The lists on ships’ invoices give amounts and indicate sorts of porcelain as plates, dishes, cups, bowls, but these do not give us a visible identity. It is only by way of salvaged finds from shipwrecks that it is possible to identify what types of porcelain shapes were actually imported to Europe. Besides several Portuguese and Spanish shipwrecks, ceramics from three early seventeenth-century VOC shipwrecks have been analysed: the Mauritius, the Witte Leeuw, and the Banda.

- 1Mocha was located at present-day Yemen on the tip of the Arabian Peninsula. The port of Gamron was situated at present-day Bandar-e ‘Abbas on the Persian Gulf.

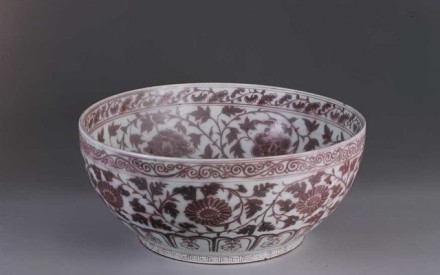

The Mauritius, shipwrecked in 1609 by a storm off Cape Lopez in the Gulf of Guinea, was on the return voyage from Asia with a cargo of pepper, zinc and only a small supply of porcelain, probably a private purchase. It was excavated by Michel L’Hour and Luc Long of the DRASSM in 1985. Of the about 215 pieces circa 165 pieces are of kraak-panelled type (fig. 1) as well as some exceptional dishes and stem cups.

The first salvaged VOC shipwreck with a substantial amount of porcelain is the Witte Leeuw, one of four ships that formed the return fleet from Bantam to Holland in 1613. During a stopover at Saint Helena Island to take in fresh water and goods, the fleet encountered several Portuguese ships. In the battle that followed, one of the cannons on the Witte Leeuw exploded and the ship sank. Marine archaeologist Robert Sténuit and the Belgian salvage company GRASP discovered the wreck in 1976. Apart from the 290 complete pieces, the 200-300 kilos of shards of identical types and shapes point to a bulk cargo. There is however, no porcelain listed on the invoice of the Witte Leeuw. This is rather a mystery as the records of the VOC are usually very accurate. On the invoice of the Vlissingen, another ship of the same fleet of the Witte Leeuw, 38,641 porcelain items are listed, and it may very well have been possible that part of its cargo was transferred onto the Witte Leeuw before leaving Bantam. It often occurred that a cargo arrived from another trade post at the last minute, and this was then divided between the return ships. The shapes listed on the invoice of the Vlissingen are identical with those salvaged from the Witte Leeuw (discussed in more detail below).

An even higher amount of porcelain was listed on the invoice of the Gelderland, which left Bantam on 25 October 1614. The Gelderland, together with the Banda and the Geünieerde Provinciën were caught in a typhoon at the island of Mauritius on their return journey at the beginning of 1615 and destroyed. The 69,057 items listed on its invoice included dishes, bowls and 25,230 brandy or gin cups that were packed in 10 casks (25.230 pimpelkens in 10 tobbe) were also included. They are identical with those retrieved from the Witte Leeuw (fig. 2). One of the other wrecked ships, the Banda, was salvaged in 1981 by the French diver Jacques Dumas. Among the porcelain is a group of dishes with similar dimensions and designs to the shards washed up on the beach from the Gelderland wreck, which could have been privately purchased as a ‘dinner set’ (fig. 3).

The ceramic finds from the Witte Leeuw

From 1979-1982 a project was organised at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to sort out and identify the large quantity of broken porcelain fragments. With the help of volunteers, it was possible to identify the majority and make a typology of the types of porcelain. The following categories were identified: common everyday Chinese wares (minyao) as rice bowls, soup bowls, small saucers (for pickles), wine cups of various sizes, a few wine pots, and some small covered pots (for ginger or pickles) (figs. 4-7). The majority of the porcelain finds was identified as what is commonly named ‘kraak ware’. During the first half of the seventeenth century, the term carrack was used by the English and kraak, kraken, or crake by the Dutch only to describe a specific type of Portuguese trading vessel and was not used to designate Chinese porcelain. The combination ‘kraak ware’ first starts to appear during the second half of the seventeenth century, but then often with the meaning of ‘old’ or ‘antique’ porcelain. The main distinction from other types of Chinese porcelain, is the non-Chinese shape such as plates, saucer dishes, clapmuts, and high bowls. A typical panel pattern in blue on a white background is painted on the rim or wall, and a central decoration mostly consists of a landscape with birds, a flower arrangement or a group of Chinese symbols such as a Buddhist fan, whisks, and others.1

Kraak-panelled porcelain was produced in various private kilns in the vicinity of Jingdezhen together with domestic wares. Most of these mass-produced items were often clumsily painted, however also high-quality pieces were produced with well-painted scenes. The latter are mostly found in the collections of the Middle East, such as the Ardebil Shrine in Iran and the Topkapi Saray in Istanbul.2

- 1It should be noted that this panel-pattern does not occur on common Chinese shapes. Chinese scholars maintain that in Chinese art terminology it is usually used to describe specific patterns with an ‘open’ aspect like a roundel, a panel or cartouche. Therefore, the term kaiguang ci (ceramics with an open decoration) is often used for kraak-panelled ware in China.

- 2The overall conclusion of Jingdezhen archaeologists is that most of the shards with the panel pattern retrieved from the Guanyinge site are of a much finer quality than those from other areas. This kiln area is now known to have been manned by well-trained potters and designers from the former Imperial factory after its closure in 1608 (the 36th year of the Wanli period). The finely decorated kraak-panelled dishes in the Ardebil and Topkapi collection were likely produced at this specific kiln site.

A variety of shapes have been found on the Witte Leeuw, below follows a sum-up of the main types:

- Large dishes with a flattened rim and having a diameter of 50 cm. There are about twenty-five to thirty pieces of this type each decorated differently with some having an exceptional central decoration (fig. 8). Another significant aspect of this type is that all bases are unglazed.

- Most favoured were dishes with a flattened rim having a diameter of 20-21 cm (fig. 9). The majority is decorated with symbols and ribbons or a bird or grasshopper on a rock, quite crudely sketched, and many dishes are warped or uneven. This type was ordered in very large numbers as they could be used as tableware, just as the common pewter dish used in Europe at that time. In 1607, a commission was sent stating: ‘we want a number of dishes …we use daily/an amount resembling our tin saucers’ (een partie gelick ons tinne sausyeren syn). The painting by Willem Claesz. Heda illustrates the use of tin/pewter plates used commonly in the Netherlands at that period (fig. 10). They even may have used as a model for the Chinese potters.

- Another shape unknown to the Chinese is a saucer dish without a flattened rim having a diameter of about 20–21 cm. The interior has round moulded medallions instead of straight panels. A large quantity of fragments was identified, amounting to about sixty to seventy complete pieces. These dishes are more finely potted than the above type and the designs are very varied and often delicately painted (fig. 11).

- There are about fifty so-called clapmuts with a diameter of about 20 cm and only a few of the smaller type (fig. 12). The Dutch name clapmuts for a shallow bowl with a flattened foliated rim is probably derived from the shape of a certain type of hat with an upturned rim often worn by the Dutch in the seventeenth century. A frequently occurring design used as a rim decoration is what is known in China and amongst art historians as a taotie mask. The shape was very popular as the name appears on most orders and shipping lists of the VOC, and was most likely to have been produced especially for the Dutch market because it was ideal to eat porridge or soup from.

- A large number of high bowls with the panel pattern (fig. 13) were sorted out from the fragments of the Witte Leeuw and come in three sizes, varying from 10 to 14 cm in diameter. They are quite different in quality, the smaller ones being more heavily potted and the larger ones more delicate and finely decorated. Various names have been applied to these bowls. VOC lists them as cammeelscop (camel cups) but this may have been a miswriting for kandeelscop (a caudle cup). Another term often applied given to them is ‘crow cup’, because the central design on the inside is always a bird on a rock. However, the bird is not a crow but a magpie (fig. 14).

- Relatively few pieces of Zhangzhou wares were retrieved from the Witte Leeuw and this may indicate these objects were either owned by crewmembers or used in the ship’s galley. Zhangzhou ware is a thicker type of porcelain and could withstand a galley’s daily usage. The large dishes are elaborately decorated with a phoenix amongst flowering peony branches, the smaller type is crudely decorated with the same design (fig. 15).

- Stoneware jars have regularly been found amongst shipwreck finds. The majority of those retrieved from the Witte Leeuw originate from kilns in Southern China; most are covered with a dark brown glaze, some having a stamped square mark with a Chinese character. These jars were used for fresh water, wine or preserving food on the long voyages (fig. 16).

The discovery and salvage of the Witte Leeuw was the first visible example of a substantial VOC cargo of Chinese ceramics and has become worldwide known. Recently a team, including the author, is setting up a digitized inventory of the ceramic finds from the Witte Leeuw based on the Rijksmuseum's official database of color images. In the future we intend to include this material on the website of Aziatischekeramiek.nl.

Literature

C.G. Brouwer, ‘The Porcelain Trade to al-Mukha during the Early Seventeenth-Century according to Dutch Accounts’, Vormen uit Vuur, 175, no. 2, 2001.

L. Blussé, ‘The Batavian Connection: the Chinese Junks and their Merchants’, in Van Campen and Eliëns (eds.) 2014, pp. 97-109.

T. Canepa, T., Zhangzhou Export Ceramics. The so-called Swatow Wares. London, 2006.

J. Dumas et Atlas Films S.A., Fortune de Mer a l’ile Maurice, Paris, 1981.

M. L’Hour, (ed.), Le Mauritius. La Mémoire Engloutie, Paris, 1989.

C. L. Van der Pijl-Ketel, C.L, (ed.) The Ceramic Load of the ‘Witte Leeuw’ (1613). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1982.

__________’Chinese Ceramics for the Dutch market: Porcelain from seventeenth Century shipwrecks of the Dutch East India Company’. Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 72, 2007-2008, pp. 43-51.

___________ ‘Kraak porcelain ware salvaged from shipwrecks of the Dutch East India Company’. In J. Welsh and L. Vinhais (eds.), Kraak Porcelain. The Rise of Global Trade in the Late 16th and Early seventeenth Centuries, London/Lisbon, 2009.

__________’Dutch Demand for Porcelain. The maritime distribution of Chinese ceramics and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) , first half of the seventeenth Century. Dissertation, Leiden University, September 2021.