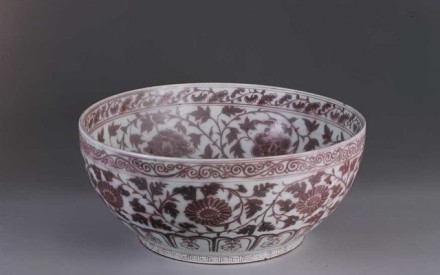

In 2015, the Rijksmuseum acquired a series of Neolithic Chinese pottery from the children of the Dutchman François Joseph Martial Bourdrez (1901–1939) (figs. 1–3). These vessels are examples of some of the earliest ceramics produced in China.

They had been on loan to the museum since 1961 and were formally transferred to collection in 2015. Bourdrez purchased the pottery in China in 1936, where he had spent several years working as an engineer for the League of Nations — a precursor to the United Nations — in China.1 The story offers an intriguing glimpse into a turbulent period in the country’s history.

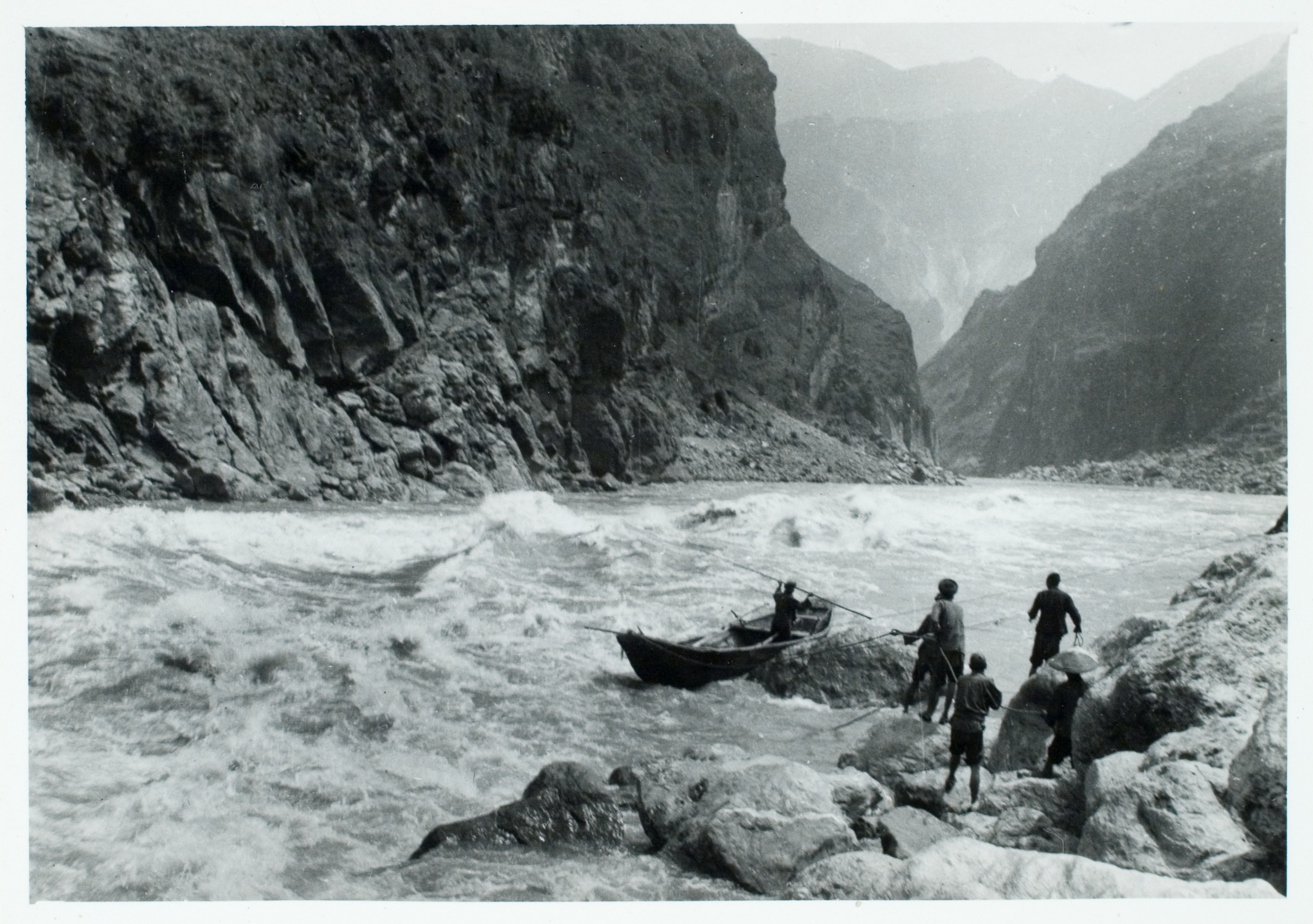

In China, Bourdrez led a major project aimed at improving infrastructure, and particularly water management. At the time, floods still claimed thousands of lives almost every year. In the disastrous year of 1931, the flooding of the Yangtze River took 400,000 lives, while the Yellow River floods claimed as many as four million. Bourdrez and his team worked closely with Chinese experts, and by combining Chinese and Western knowledge, they achieved remarkable successes. These projects were often massive undertakings involving large numbers of workers (fig. 4). The work was regularly carried out under pressure due to the constant threat of new floods.

- 1R. Boot, François Bourdrez; a struggle against mighty rivers 1901-1939, Peking, 2005.

The geopolitical situation in China during Bourdrez’s years there was particularly turbulent. The Guomindang (KMT), led by Chiang Kai-shek, held power and was internationally recognized, but the challenges were immense: the rapidly rising Communist Party posed a formidable opponent, and the Japanese threat was growing ever stronger. From 1936 onward, the overwhelming power of Japan forced the Chinese factions to cooperate partially to withstand their common enemy. A year later, the KMT government was compelled to retreat to the more southwestern province of Sichuan, where Chongqing became the temporary capital. In 1939, the KMT commissioned Bourdrez to investigate the navigability of the Yangtze River near Chongqing, as this river was vital for the transport of ammunition (fig. 5). Unfortunately, a poorly maintained boat and an inexperienced crew led to tragedy: on 10 May 1939, Bourdrez drowned after the boat struck a rock and broke in two. His body was not recovered until three weeks later. The state funeral expressed the Chinese government’s deep appreciation for the extensive work he had accomplished. In Hanoi, Bourdrez left behind his wife and two young children — a sorrowful end to a remarkably dynamic life.

During his work in China, Bourdrez travelled extensively throughout the country, often reaching remote and difficult-to-reach areas. His correspondence with his Swiss wife, Elisabeth von Meyenburgh (1905–1961), and other family members, together with an extensive collection of photographs, provides a vivid impression of these journeys.1 Naturally, waterworks (and cars stuck in the mud) appear frequently among his subjects, but he also showed an eye for natural beauty, architecture, and street scenes. Bourdrez’s working methods—his genuine appreciation for traditional Chinese techniques of river control—reveal a sincere interest in China, as do his letters and photographs. However, there is no evidence in his correspondence of any strong interest in Chinese art or in collecting it. On one occasion, he wrote to his wife that he had invited some Chinese traders to offer a bit of diversion for the European members of his team at the time: ‘I’m having an antique dealer come with his goods. It will give them some distraction.’2 From the tone of this remark, collecting seems to have been quite far removed from his own inclinations.

- 1National Archives, The Hague, Collection 567 Bourdrez, access number 2.21.287, and the website https://www.francoisbourdrez.org/

- 2‘Je fais venir un antiquaire avec des curios. Ca leur donne une distraction’. National Archives, The Hague, inv. no. 47, letter from Bourdrez to his wife, Kaifeng, 22 January 1935.

Even more noteworthy, then, is a letter he wrote to his wife on 20 June 1936, describing his arrival in Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu Province, and his intention to purchase examples of early Chinese pottery—at that time only recently discovered: ‘This afternoon I had an hour free to begin looking for the famous ‘Fischer pots’. Perhaps I’ll find something.’1 Already in his next letter he writes that he has succeeded:

'I’ve become good friends with a German priest from the Catholic mission post—a splendid fellow who has travelled all through Central Asia with a pistol at his side. He builds houses, hospitals, and churches for the mission; at the moment he is working on a real cathedral for his God. He’s doing it with a group of workers from Kansu—impossible, lazy, and clumsy men, yet somehow, he manages. Thanks to him, I can offer you two large and four small pieces of ‘Fischer pottery.’ They’re not museum pieces, but they have a fine shape, and the colour hasn’t entirely disappeared. They’re some 4,000 to 5,000 years old.’2

A month and a half later, he mentions this purchase in a letter to his mother:

‘I’m enclosing, for curiosity’s sake, a photo I took of a few old prehistoric pots that I bought from a missionary in the interior of Kansu (Mongolia) (fig. 6). They are attributed to tribes who lived there about 5,000 years ago and who may have been the forefathers of the present Chinese race. They’re made of rather brittle earthenware, painted in beautiful ‘Greek’ colours, and were used, among other things, to hold the ashes of the cremated dead.'3

- 1’C’est après midi j’ai une heure libre pour commencer mes récherches sur les fameux pots de man(…) Fischer. Peutêtre je trouverais quelqechose’. National Archives, The Hague, letter from Bourdrez to his wife, Lanzhou, 20 June 1936.

- 2‘Je suis de grands amis avec un père allemand de la mission catholique, un type magnifique qu’a voyagé partout dans l’Asie Centrale, revolver dans la poche; il bâtit les maisons, hopitaux & églises pour la mission ici; il est en train de construire un vrai cathédrale pour son Dieu, avec une bande de travailleurs de Kansu, des types impossibles, paresseux et bêtes, mais il réussit (…). Grâce à lui je puis mettre à tes pieds 2 grandes et 4 petites pièces de potterie à la manière Fischer. Ce ne sont pas des pièces de musée, mais les formes sont belles, les couleurs pas tout à fait disparues et enfin, elles ont 4000 – 5000 ans.’ National Archive, The Hague, letter from Bourdrez to his wife, Lanzhou, 29 June 1936

- 3National Archive, The Hague, inv.nr. 46, letter from Bourdrez to his mother, 14 August 1936

In his letters, Bourdrez refers to this pottery as ‘à la manière Fischer’. He was very likely alluding to Otto Fischer’s book Die Kunst Indiens, Chinas und Japans (Propyläen Kunstgeschichte IV), published in 1928.1 The first archaeological research in this region of China was carried out in 1923–24 by the Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960) and the results had been published in professional journals.2 Fischer’s book was the first work written for a broader audience in which this type of ceramics was discussed and illustrated. In the chapter on China, the very first object shown is a vase comparable to Bourdrez’s. At the time, these ceramics must have been something fascinating and entirely new to Europeans and Americans, who were mostly accustomed to the more typical Chinese (export) porcelain.

As mentioned above, Bourdrez wrote that he purchased his pieces from a German missionary who was involved in the construction of a church. In his photo albums, there is an image of a Catholic church under construction, with a missionary standing in front of it. Next to the photo, the name ‘Vater Sänger’ is written in pencil—most likely the supplier of the pottery. The Catholic mission in Lanzhou appears to have played a considerable role in collecting archaeological artefacts from China’s early civilisations. A 1948 publication by W.C. Pei and Jos Eierhoff describes the collection assembled by the mission in this field.3 They also note that Theodor Buddenbrock (1878–1959), the bishop of Lanzhou, had instructed missionaries stationed at various posts to gather this type of pottery for the archaeologist Andersson. He paid them well, which encouraged farmers and traders to see a market for such items—some even began painting undecorated pots with attractive patterns or ‘improving’ worn decorations. Even after Andersson had completed his research, new vessels continued to surface. It was probably relatively easy for Bourdrez to make his selection from this supply. Fortunately, he seems to have avoided the ‘embellished’ pieces. His examples—unsurprisingly—bear a strong resemblance to those illustrated in the article by Pei and Eierhoff.

The transport of the objects proved to be quite a challenge. Bourdrez and his team travelled by small aircraft. Now that the pots had to be brought back, there was no room left for Bourdrez’s luggage. One of the Chinese engineers had to return overland with the baggage. In a letter to his mother, Bourdrez wrote about this:

‘I had them carefully wrapped in cotton wool and jute, and managed to get them safely onto the plane from Lanchow to Nanking. I had to give up my own luggage because they took up so much space. That luggage later followed by the usual route, with a Chinese engineer—first overland, then by rail—which took two weeks, compared to seven hours by plane. Outside Kansu these pots are extremely rare; I already received an offer of S 100 for the large one.’4

In 1961, when the objects from Bourdrez’s collection were placed on loan to the Rijksmuseum, they were given a spot in the permanent display.5 For many years, they were shown there alongside Ban Chiang pottery from northern Thailand, with the aim of highlighting striking similarities between cultures separated by great distances. Today, a selection of these objects is on display in the Asian Pavilion.

For an addendum on the subsequent journey of the pots by Lucas Bourdrez, grandson of Frans Bourdrez, see here.

- 1Following correspondence on 13-01-2026 with Lucas Bourdrez, grandson of Boudrez, it appears that the interpretation of “Fischer” may in fact be different. He writes: 'The article states that my grandfather wrote that the pots are “à la manière Fischer.” I think he wrote something else, namely “à la mammie Fischer.” My grandparents had good friends with the surname Fischer. Fischer was presumably one of the many German military advisers, although I am not certain of this. Mammie Fischer was presumably the wife of this Fischer. My grandparents more often wrote in such terms about the wives of friends. It is possible that Mrs. Fischer owned such pots, and perhaps she tipped my grandfather off that prehistoric pots were for sale in Gansu.

- 2J.G. Andersson, ‘An Early Chinese Culture’, Bulletin of the Geological Survey of China 5/1 (1923), pp. 1-68; Ibidem, ‘Preliminary Report on Archaeological Research in Kansu’, Memoirs of the Geological Survey Of China. Series A no. 5 (1925); T.J. Arne, Painted Stone Age Pottery from the Province of Honan, China (Palaeontologia Sinica Series D, Vol. 1 Fascicle 2), Peking, 1925.

- 3W.C. Pei en Jos. Eierhoff, ‘On a collection of prehistoric pottery at the Catholic Mission in Lanchow, Kansu’, Monumenta Serica 13 (1948), pp. 376-384.

- 4National Archive, The Hague, inv.nr. 46, letter from Bourdrez to his mother, 14 August 1936.

- 5AK-RAK-2015-3-1 t/m -6.