From the second half of the fifteenth century, white porcelain wares were produced in large quantities for use at the royal court of the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910).

These wares replaced the typically stamped and incised buncheong stonewares (fig.1) previously used at court and government offices.1 The official kilns employed to produce these porcelain vessels, called bunwon, were located just outside the capital in present-day Gwangju, and were closely monitored by the government.2 Ritual vessels were produced in accordance with strict rules about quality, decoration and shape. The potters enjoyed more freedom when they produced ceramics for daily use and objects for aesthetic appreciation, allowing them to experiment with decorations in iron-brown, copper-red, and cobalt blue. Some of the objects produced in the bunwon kilns were even made for affluent private patrons (fig. 2).

Among the official wares, white wares with decorations using cobalt blue pigments were among the earliest and most important vessels produced in the royal kilns. These early blue-and-white porcelains were produced during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and drew inspiration from their Chinese counterparts. They were exceptionally valuable since its production was restricted; the necessary cobalt blue pigment was imported from China and was therefore very expensive, and only professional artists working for the royal family were allowed to paint the underglaze designs for these objects (fig 3-4). By the sixteenth century, regional kilns spread around the Korean peninsula started to actively produce white porcelain to meet the skyrocketing demand of white ware, however the quality did not meet that of the bunwon kilns.

- 1Buncheong (분청사기) translates to “powdered celadon” and is used to refer to a type of ceramics that holds a ‘median position’ between the production of celadon wares in the Goryeo period (918-1392) and the white porcelain wares that were produced during the Joseon dynasty.

- 2 The capital of the Joseon dynasty was Hanyang (kr. 한양, 漢陽), present-day Seoul.

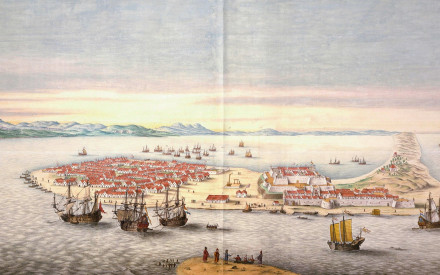

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century the general production of ceramics in Joseon Korea got disrupted due to various geopolitical events, one of them being Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Invasions of Korea (1592-1598). These invasions devastated the country and led to a shortage of raw materials; kiln sites were left in ruins and many skilled potters were forcefully relocated to Japan in order to develop the Japanese production of ceramics. The aftermath of these events made it impossible for the government-run kilns to meet the high demands for the production of white porcelain wares. As a result, porcelain produced during the seventeenth century was more greyish in colour and coarser clay was used than before. Decorations on the porcelain wares from this period were painted in iron oxide instead of the more costly and difficult to acquire cobalt blue pigment. The brushwork of these decorations possesses a playful and vibrant quality. However, most of the porcelain wares remained undecorated.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, moon jars started to be produced, but they did not become popular until the eighteenth century (fig. 5).1 These porcelain jars were originally used for storage and have a large, spherical body that is typically 40-50 cm in height. Because of its size, the moon jar is made in two separate halves which are connected at the rim with slib and covered with a translucent glaze before firing in the kiln. It was not uncommon for the vessel to collapse at the seam during the firing process due to the shrinking of the clay, and it was very rare for an almost perfect round shape to emerge from the kiln. Some jars show yellowish or orange hues which are a result of oxidation or incomplete combustion during the firing process. Moon jars produced during the reigns of King Yeongjo (r.1724-1776) and King Jeongjo (r.1776-1800) are recognised for their outstanding beauty and quality. Their reigns provided political stability and a turn away from foreign influences, enabling a cultural revival and great intellectual activity. King Jeongjo further cemented the belief that ceramics reflect the values of the official state ideology neo-Confucianism, which underpinned all aspects of Joseon society. The purposefulness and simplicity of the moon jar embodied these ideals, while its imperfect round shape represents a distinctive Korean aesthetic that flourished during a time when the country turned more inwards.

- 1From the beginning of its production, these large white porcelain jars were used as storage jars at court and government offices and contained grains, sauces, fermented foods, honey, and alcohol. At times a moon jar would also be used as a vase for flowers.

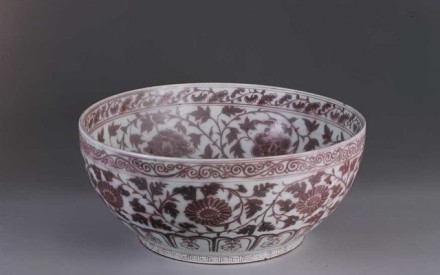

The practical learning (silhak, kr. 실학) school of neo-Confucian thought that gained momentum from the late seventeenth century was influential in how literati approached Korean art and aesthetics.1 Many scholar’s objects used by the literati class were made from porcelain, and they would often be shaped as auspicious fruits and animals, such as water droppers in the shape of a peach, rabbit or carp fish (fig. 6-8). Luxury consumption increased with the rise of affluent merchants and commoners who were eager to adopt a luxury lifestyle that used to be reserved for the literati class, government officials and court life. The potters working in regional kilns who met the rising demand of porcelain were very skilled. By the eighteenth century they were able to produce beautiful vessels with copper-red decorations under the glaze, an exceptionally delicate pigment which can easily turn grey if not fired correctly (fig. 9). In this period, cobalt pigment was mined in Korea itself, making the material more accessible than before (fig. 10).

- 1Neo-Confucianism served as the Joseon dynasty’s state ideology and emphasised social order, hierarchy, and moral virtue. Auspicious symbols such as certain animals, plants and fruits were believed to bring good fortune, harmony and prosperity which aligned with the Confucian value of maintaining social balance.

As a result, objects with decorations in underglaze blue now also became available for the new group of wealthy patrons. Among these objects dragon jars, which were originally intended for exclusive use at court, were especially appreciated. The dragons painted on these jars do not appear very frightening, they look rather friendly and are whimsically rendered through energetic brush strokes (fig. 11-12). The dynamic brushwork and imperfect shapes of porcelain wares throughout the centuries testify to a unique, vibrant, Korean aesthetic that can be seen as a reflection of the country’s culture and ideals, leaning heavily on elements inspired by its nature and surroundings.

Further reading

Berg, Eline van den, and Brugge, Annelies ter. Korea : keramiek en cultuur. Zwolle: Waanders & De Kunst, 2021.

Horlyck, Charlotte. “The Moon Jar: The Making of a Korean Icon.” The Art Bulletin

(New York, N.Y.) 104, no. 2 (2022): 118–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2022.2000269

Im, Jin-a. “Propriety and Dignity: White Porcelain.” In Earth, Fire, Soul, The Masterpieces of Korean Ceramics, 143-212. Seoul: National Museum of Korea, 2018.

Lee, Soyoung. “In Pursuit of White: Porcelain in the Joseon Dynasty, 1392–1910.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/chpo/hd_chpo.htm (October 2004)