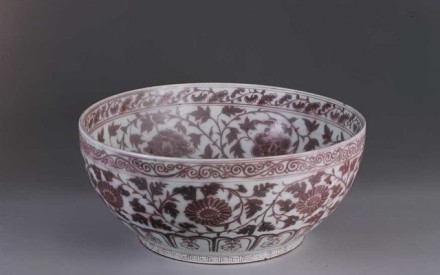

Often, when turning over a piece of Chinese porcelain from the Ming (1368-1644) or Qing (1644–1912) dynasty, you may notice Chinese characters or a symbol on its base (fig. 1). These could indicate a reign mark, a distinctive feature of Chinese ceramics that is first seen during the Ming dynasty.

The development of reign marks is closely associated with the era names of Chinese emperors. They form a unique way of indicating time in Chinese history and are also strongly linked to the development of the imperial kilns that produced high-quality ceramics for the imperial court. In general, marks are painted, engraved, or impressed on the base of the vessel, but may also be applied to the foot, body, or rim. Ceramic marks may indicate the period of an emperor’s reign, the place or purpose of manufacture, a hall name, a person’s name, a special event, or may represent an auspicious meaning. Such marks can be composed of Chinese characters but can also be a symbol based on an existing object bearing auspicious meanings, or a symbol depicting nature or representing a cultural sign (figs. 2-4). As their content, format, font and calligraphic style are indicative of the time period and of different kilns, ceramic marks can be a helpful tool for dating and identification. Because of this, ceramics with reign marks are highly sought-after by collectors. However, marks are also widely faked, meaning we cannot rely on them as proof of authenticity and need to take all properties of the ceramic object into account.

Era names and reign marks

The imperial era name (nianhao) is a system of dating based on the length of the emperor’s reign. Inscriptions on ceramics that feature era names are called reign marks (niankuan), for example Da Ming Chenghua nianzhi 大明成化年製 which may be translated as ‘made during the reign of the Chenghua emperor of the Great Ming’. Reign marks usually indicate the period of manufacture or can occasionally be a tribute to an earlier emperor. For example, during the reign of the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662–1722) various porcelains were produced bearing the reign mark of the Ming dynasty emperors (fig. 5). Such marks were a sign of respect for earlier periods and not intended as a forgery. In auction catalogue descriptions they are often referred to as ‘apocryphal’ marks. Probably the most copied apocryphal reign mark is that of the Chenghua period (r. 1465–1487), because imperial porcelain of this period was considered to be of the highest quality.

The origin of the era name system is attributed to Emperor Wu (r. 141–187 BCE) of the Western Han period (206 BCE–9 CE). The meaning of the Chinese characters chosen for the era names often reflected the hopes and visions emperors had for their regime. For example, Jianyuan (r. 140–135 BCE) was Emperor Wu’s first era name, which literally means ‘establishing a new era’. Beside changing the era name to mark the start of their reign, emperors sometimes adopted multiple era names during their reign, either to signal a new chapter after significant events, such as disasters or political turmoil, or to commemorate achievements. Emperor Wu for instance had eleven era names and Empress Wu of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) even had eighteen era names during her twenty-one-year reign (690–705).

From the Ming dynasty onward, it became practice to use only one era name for each emperor. Therefore, the era name is often used when referring to emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties. However, there were exceptions. For instance, Emperor Yingzong of the Ming dynasty had a second reign after he organised a palace coup. Similarly, Hong Taiji, the second khan of the Later Jin (1616-1636), first used the era name Tiancong and thereafter became the founding emperor of the Qing dynasty, choosing Chongde as his era name.

Imperial kilns and reign marks

The use of reign marks is closely associated with the ‘imperial kilns’ (guan yao), also known as official kilns, which produce high-quality ceramics for the imperial court. Jingdezhen became the primary production centre for imperial ceramics as early as the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). During the Tang (618–907) and Song dynasties, certain ceramics intended for court use were marked with the character for ‘official’ (guan). However, these inscriptions referred to the commissioning institution rather than an imperial kiln.

The establishment of Jingdezhen’s first imperial kiln to produce porcelain for the imperial court dates to 1278, during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). The Ming emperor Yongle (r. 1403–1424) expanded this system by appointing more imperial kilns, which on some occasions added imperial marks to their products as well. By the Xuande reign (1426–1435), marks had become a regular feature on porcelain pieces made in imperial kilns. These marks served as symbols of imperial quality, signifying that the object met the court’s exacting standards. Beyond ceramics, reign marks also appeared on objects crafted in other imperial workshops, such as lacquerware, glass, and bronze. In these contexts, the marks functioned similarly—as indicators of superior craftsmanship and official provenance, tying the object to the emperor’s reign. This system not only reinforced the prestige of imperial production but also created a legacy of artistic excellence associated with the emperor’s era.

While some ‘civil kilns’ (min yao) also produced ceramics with reign marks, the style of their marks was generally relatively sloppy and not as written as neatly as those produced by the imperial kilns, except for orders that were commissioned by the imperial court. This sometimes happened if an order was too large to be delivered in time by the imperial kilns. Consequently, ceramics with reign marks are usually classified as objects produced in the imperial kilns during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

How to read reign marks: vertical writing

Chinese texts are traditionally written and read vertically, going from top to bottom, and ordered from right to left (fig. 5). In some cases, however, the characters are written horizontally, which are read right to left (figs. 6-7). Reign marks are usually found on the base of objects, presented in columns of two or three characters. When the marks are placed on the foot rim or mouth rim of the vessel, the characters are usually written in one horizontal row as seen in figure 7.

In most of cases, reign marks on ceramics are written either in normal script (kaishu) or in archaic seal script (zhuanshu) (figs. 8-9), painted under or over the glaze, though occasionally the mark is moulded in relief. They generally follow a fixed format, consisting of four or six characters. The first two characters of a six-character mark stand for the dynasty, for instance da Ming 大明 (the great Ming dynasty) or da Qing 大清 (the great Qing dynasty, figs. 10-11); the next two characters indicate the era name, such as Chenghua 成化 (fig. 10) or Kangxi 康熙 (fig. 11); the last two characters are usually年製 (nianzhi), meaning ‘made in the period’. In four-character reign marks, the first two characters indicating the dynasty are omitted and in some cases the third character is changed from nian 年 to yu 御. Yuzhi 御製 refers to ‘made by imperial order’.

Conclusion and further reference

Reign marks are commonly found on ceramics produced in the imperial kilns of the Ming and Qing dynasties. One would not expect to find a reign mark on ceramics produced before this period. Although they are often copied, reign marks can be very helpful in dating and authenticating ceramics, as they can be traced back to a specific period according to the name of each emperor's era. There are many publications and online sources in which collectors and specialists share their knowledge of reign marks. For example, Gerald Davidson’s Marks on Chinese Ceramics (2021) is a comprehensive reference guide for a broad range of ceramic marks. High quality photographs of reign marks can also be found in online museum collections databases and some auction house catalogues.

Literature

Davison, Gerald. The New & Revised Handbook of Marks on Chinese Ceramics. Castle Cary: Gerald Davison Ltd, 2010.

Hunt, Kate. Demystifying Chinese Reign Marks: Everything You Need to Know to Get Started. Christie’s: Asian Art & Collecting Guide, 2020. https://www.christies.com/features/Reign-marks-on-Chinese-ceramics-An-expert-guide-8248-1.aspx?sc_lang=en&lid=1

Nilsson, Jan-Erik. Gotheborg.com. https://gotheborg.com/marks/marksintroduction.shtml

Pater Gratia Oriental Art. https://www.patergratiaorientalart.com/home/1407

Sima, Qian. Records of the Grand Historian. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.