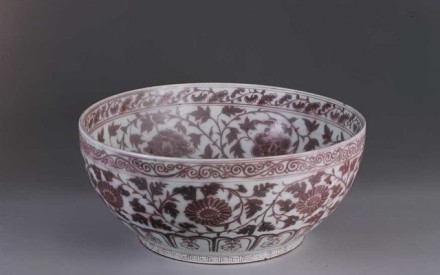

Royer’s porcelain collection in the Rijksmuseum includes a number of objects decorated with a combination of enamel colours and underglaze blue, such as this vase and covered box (figs. 1-2). This porcelain was made during the reign of Emperor Shunzhi (1644-1662). During this period the overseas trade in Chinese porcelain fell sharply due to the struggle in China between the Manchus, who had proclaimed the Qing dynasty in 1644, and the supporters of the old Ming dynasty, who continued to resist the new rulers in southern China until 1684.

Jingdezhen, the city where porcelain was made, was hardly affected in the early years of the struggle, but production was severely curtailed by a major revolt by Ming sympathisers in 1675. Until then, the main problem had been that exports of Chinese goods from southern China were largely hampered by the new Qing authorities. They wanted to prevent Ming supporters from profiting from that trade. The last large consignment of porcelain arrived at the Dutch trading post on Formosa (present-day Taiwan) in 1647. It is remarkable that despite these obstacles, this polychrome Shunzhi porcelain can still be found in several old European collections, including Royer’s. How did it end up there and who brought it?

Polychrome Shunzhi in China

Porcelain was already being decorated with enamel colours for the domestic market in the Ming dynasty, especially during the Wanli period (1573-1620) (fig. 3), and apparently there was a resurgence of demand for it in the Shunzhi period. It is notable that by then, part of the decoration was first painted in underglaze blue, in a way that took into account additions in other colours that were applied only after the object had been fired for the first time. Although highly creative, porcelain manufacture and trade were above all, commercial pursuits. The main buyers in the Shunzhi era were private Chinese individuals, as there were temporarily no large orders from the court due to the internal strife. This new client base of private individuals stimulated innovation. Porcelain decorated with scenes from illustrated novels and plays became very popular. This trend had started somewhat earlier, as seen in the blue-and-white Transitional porcelain from the preceding period (c. 1635-1650). Apart from this Chinese clientele, however, porcelain makers and dealers needed export sales to generate enough income. Official overseas trade was impossible, so these merchants looked for ways around the blockade. Traders from Huizhou appear to have played an important role in the distribution of porcelain from Jingdezhen, including to port towns from where the porcelain was shipped.1 Despite difficult conditions, they succeeded, but the volume was not very large. They could depend on a constant demand from Europe. When the quantity of polychrome Shunzhi pieces in Europe is compared with the large numbers of blue-and-white plates, bowls, dishes, bottles, vases, scrolls and jugs from the period up to 1647, this disparity becomes immediately clear. These polychrome pieces were exclusive and probably expensive.

- 1See McDermott 2013, Gerritsen 2014, p. 93, and idem 2020, p. 206.

Overseas trade

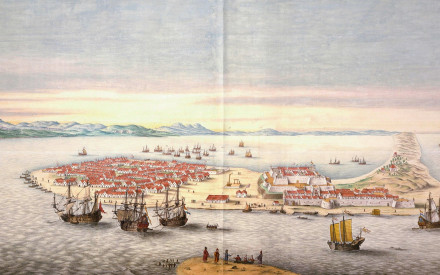

How did porcelain from mainland China reach Dutch merchants in Formosa? There is no single answer to this, but a tour of the various options provides a good impression of the various opportunities and difficulties affecting trade in the South China Sea, how it was dominated by Asian traders, and how dependent the Dutch were on them.

The Zhengs

Zheng Chenggong (also known as Koxinga, 1624-1662) controlled trade in the South China Sea at the time. His family had built up a large network that earned them so much that they had become a formidable opponent for the Qing dynasty that was established in 1644. The Zhengs formed an unofficial state in southern China in the 1640s and 1650s, and Zheng was its ‘ruler’. Selling Chinese silk in Japan and exporting Japanese silver to China was by far the most important source of income. Both the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Zheng Chenggong wanted to control this commerce, and eventually the Zhengs succeeded at the expense of the VOC. Other products followed in the wake of the silk-for-silver trade, including possibly polychrome Shunzhi porcelain. Even though the Zhengs were calling the shots in the South China Sea, they could not possibly handle all the transportation themselves, so they recruited independent merchants, who paid taxes in exchange for protection. Helped by the VOC, which issued permits to Dutch freemen and Chinese traders in Batavia from 1648 onwards to sail to Japan, these merchants had no trouble finding Dutch customers in Japan and Batavia for their merchandise.1 However, opportunities to sell porcelain deteriorated during the Shunzhi period. Hostility between the Zhengs and the VOC increased as the Zhengs granted the VOC less and less trade. At the same time, the Qing authorities increasingly closed off the coastal area of southern China in an effort to restrict the Zhengs’ trading opportunities. This also made it more difficult for Chinese merchants from southern Chinese ports to deliver goods to Dutch buyers, although trade never really came to a standstill. Archive research has shown that Qing supervisors regularly ‘cooperated’ with Zheng merchants (albeit in secret) and earned money from it. Additionally, there are historical records of severe punishments for Chinese boatmen who traded without permission from the Zhengs. This proves, on the one hand, that in addition to this clandestine cooperation, there was supervision by the Zhengs, but also that this supervision was sometimes inadequate. The reports deal with traders who were caught, but undoubtedly others sailed through the cracks and of course were unrecorded.2 In short, trading in polychrome Shunzhi porcelain was not impossible, but it was very difficult.

Southeast Asia and Canton

The Qing’s sealing off the Chinese coast and the war between Qing rulers and Ming sympathisers ended the supply of Chinese silk to Japan. This was a major setback for the aforementioned all-important silk-for-silver trade with Japan. A solution was found in Bengal and various ports in Southeast Asia where local silk was sourced. Zheng Chenggong was at the height of his power and sent trade fleets to these ports to buy the silk. But the VOC also had its outposts there. These were important trade hubs where Dutch merchants could also purchase polychrome Shunzhi porcelain.3 #_ftn3" title>[3] Meanwhile, the VOC’s attention shifted from Zheng Chenggong to the new rulers in China, the Qing. A trading base in China had always been high on the VOC’s wish list. Formosa had fulfilled this dream for some time, but Zheng seized the Dutch colony in 1662. Even before then, the VOC realised that Formosa would become too expensive to sustain and that the future lay with the Qing rulers. Between 1652 and 1660, VOC ships sailed several times to Canton (present-day Guangzhou), which was in Qing hands, to establish contacts and try to trade. The Qing had entrusted the Han Chinese Shi Lang (1621-1696) and Geng Jiomao (n.d.) with power there.4 They were loyal to the new leadership, but also looked out for their own financial interests and allowed a select group of merchants to trade with the Dutch. So here, too, was an opportunity for Chinese merchants to sell their porcelain to the Dutch. Trade prospered in the early years, until the Qing authorities tightened their grip on the region.

- 1Jörg 2014, p. 139, Blussé 1986, pp. 117, 119. In this respect, the VOC worked like the Zhengs: in return for payment, traders were given permission to trade and (to some extent) protection at sea.

- 2Vermeer 1990, pp. 236-237, 241; Xing Hang 2016, pp. 93-95.

- 3Xing Hang 2016, p. 93

- 4Wills 1974 and 1984, Xing Hang 2016, pp. 153-154.

Dutch demand

There is a rare clue in the VOC archives that provides insight into the demand for polychrome porcelain in the Netherlands. In 1648, the Amsterdam Chamber of the VOC wrote to the governor-general and councils in Batavia that ‘lovers of rare porcelain are clamouring for porcelain painted green’.1 Considering the predominance of green in Shunzhi pieces like this vase (fig. 4), one may assume that these were the objects they were referring to, especially because Dutch clients had only seen blue-and-white porcelain up to that point. The fact that the VOC noted in 1648 that this polychrome porcelain was in great demand indicates that private individuals had by now been introducing this type for some time. The letter continues with a request to order dishware painted in this manner in Formosa, but this never materialised. Flatware (by far the bulk of the VOC’s porcelain trade) with this type of decoration is virtually unknown (unlike the slightly later early Kangxi polychrome dishes). That the trade in polychrome porcelain was handled by private individuals, in which Chinese merchants took the lead, and that it encompassed the entire area around the South China Sea up to and including Batavia, is evidenced by an entry in the daily registers of Zeelandia on Formosa from 1654. A Chinese porcelain merchant from Anhay, named Cinko (n.d.), asked what the VOC wanted. He would sail to Japan to have it made there.2 #_ftn2" title>[2] As explained above, it is clear what the VOC was looking for: polychrome porcelain. Small-scale production started in Japan (fig. 5), eventually resulting in Kakiemon and Imari porcelain – something quite different from polychrome Shunzhi, but they are members of the same family. It would be several years before the VOC could buy polychrome porcelain in Japan – production there first had to get underway and be scaled up. For the time being, the VOC left this trade to private individuals and customers could be better served with polychrome Chinese wares offered for sale ‘everywhere’ and thus also in Japan.

If this reads like a somewhat muddled overview, it’s because it was a chaotic time, a time of trial and error, especially for Chinese merchants who needed outlets. The character of that period is reflected in the assortment of Shunzhi pieces in old collections in the West. They are diverse objects, Chinese in shape and decoration and sometimes of very high quality, but there are not that many of them. The aforementioned, often-publicised covered box (fig. 2) from the Rijksmuseum’s Royer collection is a perfect example of that highest quality. The small covered vase (fig. 4), also mentioned above, together with two rolwagen vases (fig. 6), comprise a very early example of a garniture. Such pieces were never traded as lots by the VOC itself, but always privately by VOC officials who knew that there would be plenty of buyers for them in porcelain-obsessed Europe, even if they were expensive.

Literature

Leonard Blussé, Strange company: Chinese settlers, mestizo women and the Dutch in VOC Batavia, Leiden 1986.

Anne Gerritsen, The city of blue and white: Chinese porcelain and the early modern world, Cambridge, 2020.

Anne Gerritsen, ‘Merchants in 17th-century China’, in: Jan van Campen and Titus Eliëns (red.), Chinese and Japanese porcelain for the Dutch Golden Age, Zwolle, 2014, pp. 87-96.

Christiaan Jörg, ‘A change in taste: the introduction of enameled export porcelain in the 17th century’, in Jan van Campen and Titus Eliëns (red.), Chinese and Japanese porcelain for the Dutch Golden Age, Zwolle, 2014, pp. 129-150.

Christine Ketel, Dutch demand for porcelain: the maritime distribution of Chinese ceramics and the Dutch East India Company (VOC), first half of the 17th century, N.pl., 2021.

Joseph P. McDermott, The making of a new rural order in South China. Vol I Village, Land, and Lineage in Huizhou, 900-1600, New York, 2013.

E.B. Vermeer (red.), Development and decline of Fukien province in the 17th and 18th centuries, Leiden etc. 1990.

John E. Wills Jr., Pepper, guns and parleys: the Dutch East India Company and China, 1662-1681, Cambridge MA, 1974.

John E. Wills, Jr., Embassies and illusions: Dutch and Portuguese envoys to K'ang-hsi, 1666-1687, Cambridge MA, 1984.

Xin Hang, Conflict and Commerce in maritime East Asia: the Zheng Family and Shaping of the Modern World c. 1620-1720, Cambridge 2016.