Diplomatic gifts have been part of international relations since ancient times. They may represent, among others, more or less noble motives of power and authority, friendship, request for help, apologies, bribes and tricks. They were, and still are, political art.

The material exchange of diplomatic gifts promoted the circulation of luxury goods in intercultural contacts.1 This article will examine Chinese porcelain as a diplomatic gift in the early modern period; the Ming period in China from 1368 to 1644, the Renaissance in the Western World, and the early modern period in the Islamic empires of Mughal India, Safavid Iran, Ottoman Turkey and Mamluk Egypt from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries. Three case studies will be used:

1) A large vase (fig.1) painted in cobalt blue with a powerful and vibrant dragon, made during the reign of the Chinese Yongle emperor (r. 1402-1424) at the beginning of the fifteenth century, and probably given as a diplomatic gift to a Muslim ruler on the Southeast Asian archipelago, now Indonesia. The vase is preserved in the collection of the Princessehof Museum in the Netherlands.

2) A large celadon vase and a big celadon dish (fig. 9-10), given by the Sultan of Egypt to the House of the Medici in Italy. The gift is documented through an inscription on the base of the large dish and can be dated to 1487. These objects are now preserved in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes, part of Palazzo Pitti in Florence.

3) A group of Chinese porcelain (fig. 14) given in 1590 by the Medici as a diplomatic gift to the court of Saxony at Dresden, Germany. The gift is documented in the Dresden Kunstkammer inventories and preserved in the Porcelain Collection at Dresden.

- 1For a general overview of diplomatic gifts see Brummell 2022

The Princessehof Dragon vase

Nanne Ottema (1874-1955), founder and lifelong director of the Princessehof Museum in Leeuwarden , acquired the spectacular Princessehof dragon vase in 1935.1 He had discovered it in a small antique shop in Rotterdam. Together with his vase, Ottema got the information that it was originally found on the Sangir or Sangihe islands in Indonesia. This refers to a group of seventy-seven volcanic islands stretching north of Sulawesi into the direction of the Philippines. How did this piece of porcelain- of which only four comparable pieces are known, preserved in the palace collections in Beijing and Taipei – travel from China to Indonesia and finally to Friesland? In order to find out we first have to go back to the early Ming dynasty in China when this vase was made in the imperial kilns of Zhushan, Jingdezhen, and explore how this precious vessel travelled from China to the Sangir Islands.

The Yongle emperor (fig. 2) was the Ming dynasty’s founder’s son. In 1403, he made himself emperor, choosing the reign title of Yongle (meaning perpetual happiness). In 1405, the emperor sent out his trusted admiral Zheng He (1371-1433), commanding a gigantic fleet of ships, to the far borders of the known world. These legendary Seven Sea Voyages lasted until 1433 (fig. 3). The mission was to overwhelm and convince foreign people and rulers of the power of the glorious Ming dynasty and its Yongle emperor. Zheng He and his fleet sailed to Southeast Asia, India, Sri Lanka and the African coast, to the Red Sea, and even close to Mecca and Medina. Several voyages to what is now Indonesia are recorded.2 Most of the diplomatic gifts Zheng He presented to the foreign rulers were probably silk and porcelain, representing China’s superior and most prestigious products. It is therefore very likely that the dragon vase now in the Princessehof collection was one of the diplomatic gifts carried by Zheng He in the early fifteenth century to one of the Muslim rulers of the Indonesian archipelago. In the early twentieth century, when Indonesia was under Dutch colonial rule, this vase was somehow ‘acquired’ there and brought to the Rotterdam antique shop. There , Nanne Ottema discovered it and subsequently added it to the Princessehof’s collection. A spectacular global biography of a Chinese vase.

Chinese Porcelain at the courts of Islamic Rulers and in Renaissance Italy

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the courts of Central Asia - like the Timurids and the Mughal court in India - together with the Persians, Ottomans and Egyptian rulers in the Middle East, were the most important clients for Chinese porcelain. Chinese porcelain was used for status display, as diplomatic gift, but mainly for banquets. A miniature from the late sixteenth century shows the Mughal emperor Akbar (1542 –1605) receiving Persian ambassadors, who are presenting him with valuable diplomatic gifts (fig. 4). On the left, we see the preparations for the banquet: large Chinese dishes of celadon and blue and white porcelain, some with gold and silver covers, have been placed on a red carpet. The – still empty – blue and white dish must have been of an enormous size.

Today, more than 20,000 pieces of Chinese ceramics, mostly blue and white porcelain and celadon, are preserved in the collection of the Topkapi Saray in Istanbul. With around 1350 pieces, the number of Chinese celadon is enormous.1 Celadon wares were particularly appreciated because of their green glaze – green symbolizing the Islam. The Ottoman rulers were using Chinese porcelain as luxury tableware. A miniature (fig. 5) depicts the reception of the Polish ambassador at the Ottoman court in 1677. The banquet is served on large Chinese dishes. At ceremonial banquets at the Topkapi palace food was mostly served on large celadon serving dishes, suiting Muslim communal eating habits. We know from descriptions that at some formal banquets more than 800 pieces of celadon were used. Besides its revered green colour, celadon was believed to crack or ‘sweat’ if poisonous food was placed on it - every ruler’s nightmare – making this type of ceramic even more valued.

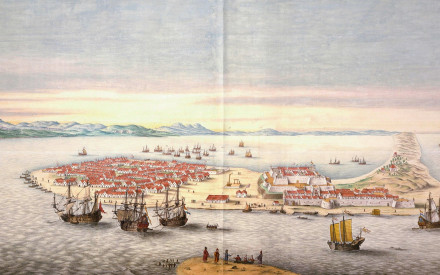

Chinese porcelain first came to Europe, especially to Italy, via the countries of the Middle East. Italian merchants conducted a vigorous trade with the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Egypt and Syria. Venice, as a cosmopolitan ‘Eastern City’, played a key role in this trade.2 From this city Marco Polo (1254-1324) set out to the Far East in 1271. A magnificent painting (fig. 6, detail), now in the Bodleian Libraries Oxford, depicts this scene. Marco, his father and his uncle are on the brink of their departure from Venice, bound for China, the Mongol empire of the Yuan (1279-1368). During his stay in China, Marco Polo had seen white or white glazed Chinese ceramics near the port of Quanzhou in Fujian province and referred to it in his travel account as porcellane, a word used in Italian for cowry shells. The word probably originates from porcellus, referring to the whitish pink colour and hunched back of small piglets, probably because these shells resembled this colour.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Venice was the cosmopolitan centre of the meeting of East and West, the capital of exotic luxury goods, where Chinese porcelain was highly appreciated.3

This is represented in two important paintings: The Adoration of the Magi by Mantegna (fig. 7), and the Feast of the Gods by Bellini (fig. 8). Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) painted the Adoration of the Magi around 1500. The first wise man’s gift is a blue and white cup filled with pieces of gold. The decoration with lotus scrolls indicates that this could well be a fine fifteenth century Chinese porcelain cup. The famous Feast of the Gods by Giovanni Bellini (1430/35-1516) and Titian (1488/90 -1578), dated 1514, illustrates a festival attended by classical mythological deities. The Greek gods and goddesses are feasting and dining from food served on Chinese porcelain. The blue and white bowls with their decorations of lotus scrolls are again those of fifteenth century Chinese porcelain.

These paintings are in fact the earliest depictions of Chinese porcelain in European painting. The detailed precision with which Giovanni Bellini painted the exotic Chinese porcelain in his Feast of the Gods makes it obvious that he had actually seen the ‘real thing’. It would indeed not have been difficult for Bellini to have access to Chinese porcelain preserved at the Doge’s Palace in Venice. He had painted the portraits of both the Doge Agostino Barbarigo (1419-1501) and his successor Pietro Loredano (1436-1521) and it must have been during these visits in preparation of those portraits that he had also seen these porcelain pieces in their collection.

Chinese Celadon as a Gift from the Egyptian Sultan to the Medici

In Florence the Medici emerged as the earliest actual collectors of Chinese porcelain in Europe. Records show that the collection of Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449-1492), also known as Lorenzo il Magnifico, included fifty-one pieces of Chinese porcelain. Most of it had come into his collection as diplomatic gifts. An example is the gift of some twenty pieces of Chinese porcelain given in the year 1487 by the Egyptian Sultan al Ashraf Quaitbay (1416-1496) to win the support of the Medici. Two pieces from this gift are still preserved at the Treasury of the Grand Dukes part of Palazzo Pitti in Florence: a large celadon vase, which can be dated to the late Yuan or early Ming dynasty, and a celadon dish dating of about the same period (fig. 9- 10).1 The large celadon dish has an inscription on the base, which reads: ‘Cois Bey d’Egitto mando da finimento da terra d’Egitto a Lorenzo il magnifico (The sultan of Egypt sent this from Egypt to Lorenzo il Magnifico to embellish the (diplomatic) relations.’

- 1For Chinese porcelain in the collections of the Medici see Spallanzani 1978 and Morena 2005

The Medici Gift: Chinese Porcelain as a Diplomatic Gift from the Medici to the Elector in Dresden, Saxony

The Medici, particularly Lorenzo il Magnifico, had made Florence the centre of an international diplomatic network. One of his successors, Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici I (1549-1609) (fig. 11) was the greatest collector of his time. His famous collection of Greek and Roman sculpture, bronzes and paintings were housed in the Villa Medici in Rome. In the year 1587 Ferdinando became Grand duke of Tuscany and moved his collection from Rome to Florence, where it was housed in the Palazzo Pitti. Based on the preserved inventories we may conclude that he passionately collected ceramics, including Chinese porcelain. It has to be mentioned however, that it is sometimes difficult to discern if the porcellana, mentioned in the inventories and lists, refers to Italian majolica, Islamic fritware or Chinese porcelain. In October 1571 Ferdinando gave his sister Isabella (1542-1576) eighty pieces of porcellana de l’Indie. Indie in this period is referring rather vaguely to the ‘Far East’ and these gifted pieces were therefore very probably Chinese porcelain.

By 1590, the collection of Chinese porcelain of Cardinal Ferdinando seemed to have grown to more than 500 pieces. In this year, on 26 February, Ferdinando sent fourteen pieces of fine Chinese porcelain to Christian I, Elector of Saxony (1560-1591, fig. 12). It was a most fragile diplomatic mission, a long journey from Florence, over the Alps to the north, to far away Dresden. The Saxonian electors of the sixteenth century had the ambition to turn Dresden into a princely city and to establish themselves as rulers of European importance. This meant modernisation, particularly in the cultural field, and modernisation meant ‘Italianisation’. In 1586, Christian I had become the Elector, to rule only a short period of time. As a great collector, his ambition was to enlarge the Dresden Kunstkammer, the treasury, to give it European importance. The Medici were interested in maintaining a good relationship with German rulers, who could provide them with both skilled mining and artillery specialists and political support. Upon assuming the title of elector of Saxony, the Medici sent three works to Christian I of the famous sculptor Giambologna (1529-1608) from Florence to Dresden. One of his masterpieces, the figure of the messenger of the Gods, Mercurius or Mercury, is still one of the highlights of the Green Vault, the Dresden Kunstkammer. In 1590 the earlier mentioned diplomatic gift from the Medici arrived at the Dresden court of Christian I.1 The list of these gifts, written at the Medici court in Florence, is still preserved today (fig. 13). We know from these registers that three boxes were packed for this diplomatic mission: one again with bronze sculptures and paintings, one with Chinese porcelain and an extra box containing typical Italian gourmet food still highly appreciated today, like Parmesan cheese, olio dolce (sweet oil), different kinds of prosciutto, special ham, salami and ‘salted geese’. To swallow this more pleasantly, the box contained wines like Graeco di 48 anno (Greek wine, 48 year old), Sicilian wine, Trebbiano. The inventory of the Dresden Kunstkammer from 1595, preserved in the archives, lists the Medici gift of Chinese porcelain as follows: ‘Ahn Italianischenn Trinck und anderen Geschirren welche anno 1590 von dem Hertzogenn von Florenz vorehrte worden (Italian drinking vessels and other vessels, which were given in the year 1590 by the Duke of Florence).’ The register of the gifts includes fourteen Chinese porcelains and objects made of gold and silver. Most of the Chinese porcelains are not specifically referred to, the register just says: ‘una schodella di porcelana (one porcelain bowl).’ However, comparing the lists from Florence and the Dresden inventories, it is not difficult to identify individual pieces.

- 1For the Medici Gift see Stroeber 2006, pp. 11-19, and Stroeber 2012

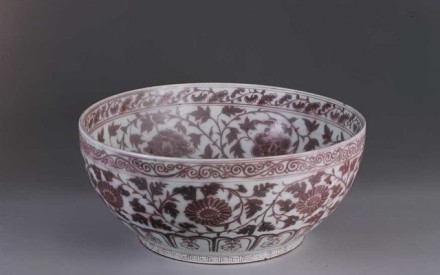

A group of eight pieces from the Medici gift is still preserved and on display at the Porcelain Collection in Dresden (fig. 14). They represent a most remarkable ensemble – some of the first mysterious Chinese ‘porcelains’ that made their way over the Alps to the North. We see, from left to right: two so-called kinrande bowls, green and red glazed with gold decorations on the exterior; a most interesting small ewer in the shape of a crayfish; a ewer in the shape of a phoenix; two blue and white bowls and on the right a blue and white lidded bowl. A strangely shaped object is the small lantern in the shape of a boat painted in green and yellow, with the figure of the Chinese god Guixing standing on it. The ewer in the shape of a phoenix is spectacular. Apparently, the Dresden scribe was – quite understandably – not very familiar with a Chinese phoenix, so he mistook it as a dragon and listed this vessel as a porcelain jug in the shape of a dragon, with gold and colours added. The interesting little crayfish shaped-vessel (fig. 15) is a bizarre type of vessel, which, during the early Modern Period, travelled from southern China where it was made, around the globe.1 It is only about 10 cm high. In the description of the Medici collection from the year 1579 it says: ‘una peparola di porcellana a moda di gambero, dorato (a vessel for pepper made of porcelain in the shape of a crayfish, with gold).’ The term peparola – which means something like a small pepper-pot – seems quite surprising. We would think that the vessel was used to pour water - a kind of water dropper. But obviously the Medici put pepper – at that time quite an exotic and very expensive commodity - into the opening at the back and poured it from the opening at the crayfish’s mouth. This comes as no surprise, as we know that the Medici kept porcelain objects not only as collectors’ items or for display, but actually used them at the table.

These three case studies are only one aspect of the history of Chinese porcelain as a global luxury good in the early modern period. More research will enrich not only our knowledge on the history of Chinese porcelain, but also that of the history of global trade, so familiar today. To quote John Carswell from his wonderful book Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain around the World: ‘I can think of no other commodity that can so perfectly illustrate the complexity of human relations in the past, and the interaction of civilizations at the opposite ends of Asia and indeed around the world.’

- 1See Ströber 2018

Literature

Paul Brummell, Diplomatic Gifts: A History in Fifty Presents. C. Hurst & Co. Publications. London 2022

Stefano Carboni, Venice and the Islamic World. 828-1797. New Haven 2007

John Carswell, Blue & White. Chinese Porcelain Around the World. London 2000

Anna Grasskamp and Monica Juneia (eds.), EurAsian Matters. China, Europe and the Transcultural Object. 1600-1800, Munich Berlin 2018

Regina Krahl and John Ayers, Ceramics in the Topkapi Serail Museum. Istanbul, 3 vols. London 1986

Huan Ma. Ying-yai sheng-lan. The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores, 1433. Transl. J.V.G. Mills, Cambridge 1970

Rosamond Mack, Bazaar to Piazza. Islamic Trade and Italian Art 1300 – 1600, University of California Press. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 2001

Francesco Morena, Dalle Indie Orientali alla Corte di Toscana: Collezioni di arte cinese e giapponese a Palazzo Pitti, Florence 2005

Marco Spallanzani, Ceramiche Orientali a Firenze nel Rinascimento. Florence 1978

Eva Ströber. The Earliest Documented Ming-Porcelain in Europe: A Gift of Chinese Porcelain from Ferdinando de’ Medici (1549-1609) to the Dresden Court. International Asian Art Fair 2006

Eva Ströber. Two Important Porcelain Pieces from the Yongle Period. In: Aziatische Kunst, no. 1 (March 2013), 20-27

Eva Ströber. Porzellan als Geschenk des Grossherzogs Ferdinando I de‘ Medici aus dem Jahre 1590, in. D. Syndram and M. Woelk (eds.), Giambologna in Dresden - Die Geschenke der Medici. Munich Berlin 2006

Eva Ströber. Ming. Porcelain for A Globalized Trade. Stuttgart 2013. 46-48

Eva Ströber. A Global Crayfish: The Transcultural Travels of a Chinese Ming Dynasty Ceramic Ewer. in: Anna Grasskamp and Monica Juneia 2018. 203-220