133,000 individual pieces of porcelain. That is the size of the order sent in 1459 from the imperial court in Beijing to the supervisors in charge of the porcelain kilns in Jingdezhen. 133,000 perfect pieces of porcelain had to be shaped, decorated, glazed, fired, packed and safely transported from the southern province of Jiangxi to the forbidden city in Beijing, where they were to be used in the various public and private spaces of the imperial palace.

The imperial court could place such a large order, because the kilns in Jingdezhen were ‘imperial’ kilns, producing porcelains specifically for the personal use of the emperor and his household as well as for the imperial administration as a whole. Porcelains were used everywhere, in imperial rituals and banquets, in offices and kitchens, in the storehouses of diplomatic gifts and even for fire prevention. But such a large order was difficult to fulfil: the required quantities of clay and firewood alone put pressure on local resources and the demand for highly skilled workers outstripped supply, so that the order was reduced to a more manageable 80,000 pieces later that year.

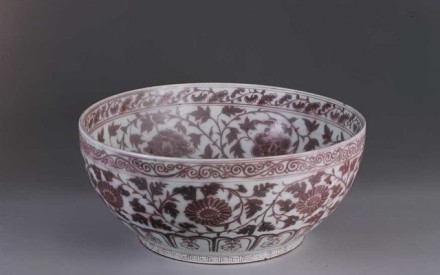

Jingdezhen had not always been the main site of imperial ceramic production. In fact, when it gained the name of Jingdezhen, during the Jingde reign period (1004-1007) of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1126), it was one of several ceramics production sites scattered throughout the empire that all produced fine ceramics that appealed to the tastes of the Song emperors. The preference during the Song dynasty was for monochromes and for fine clays that turned white when fired (fig. 1). The clay in Raozhou, the area where Jingdezhen was located, was smooth, strong, and brilliantly white when fired, which made it especially attractive for translucent glazes (fig. 2), and was probably responsible for the first imperial demands for Raozhou porcelains that continued for many centuries thereafter.

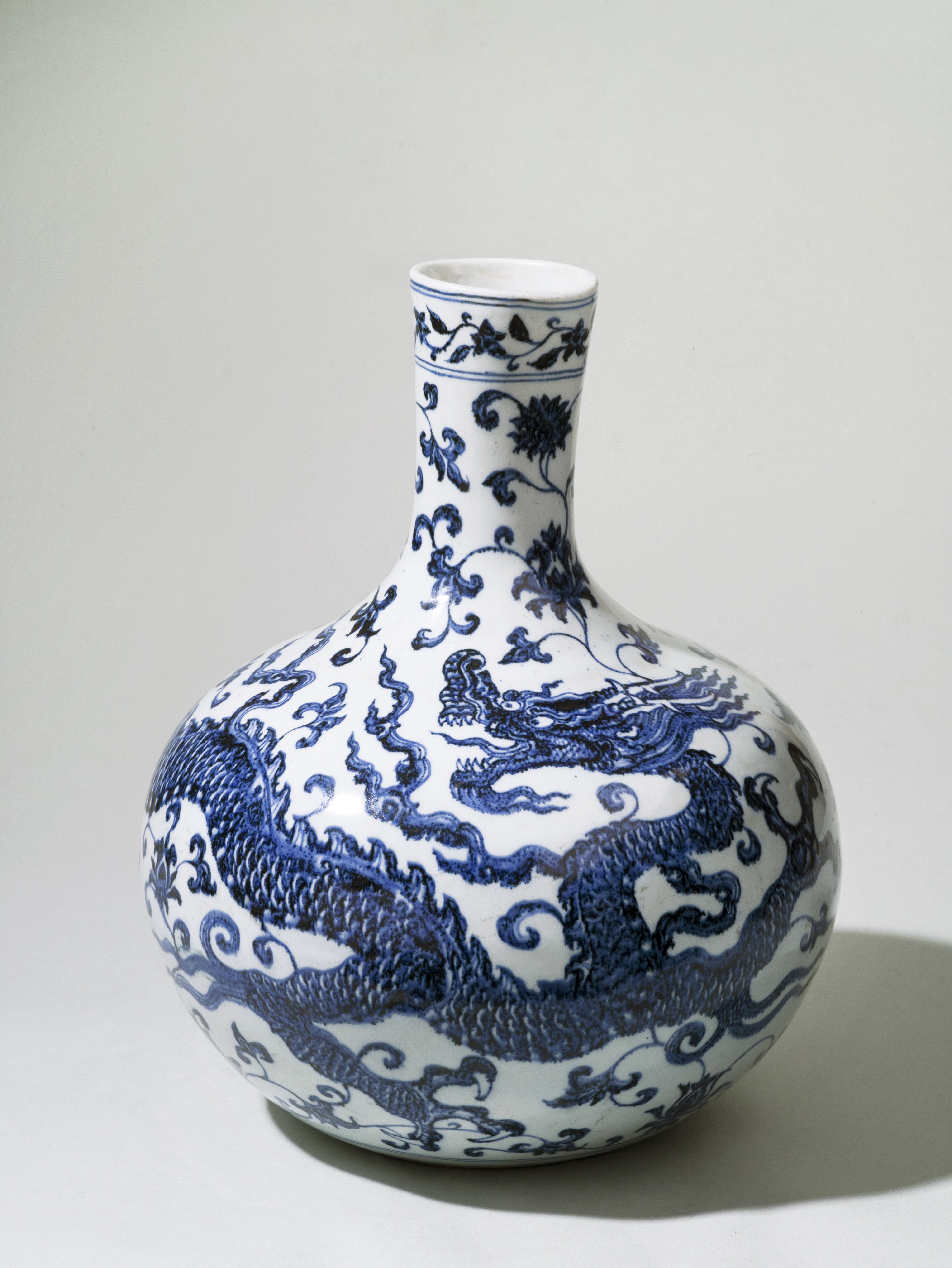

The supply of that clay was not endless, however, and over the course of the fourteenth century, potters in Jingdezhen started to combine their clay with kaolin, sourced from the nearby Gaoling mountains. That combined material was malleable but strong and kept its shape when fired at extremely high temperatures. This created the perfect surface for another innovation: the application of cobalt decorations under the glaze, producing the iconic blue-and-white ceramics desired all over the globe (fig. 3). As demand grew, both from the imperial court and further afield, so did the production site. In the sixteenth century, there were hundreds of kilns in Jingdezhen, with thousands of workers producing the vast quantities of porcelains that the imperial court demanded. Most of this labour was drawn from the population of the surrounding counties, and very few of these labourers were skilled potters, but they were essential for the production of ceramics on such a large scale. They worked in specialised workshops, focusing just on the chopping of firewood, or the purification of clay, or the grinding of cobalt. No piece of porcelain was crafted by a single potter; each piece the outcome of a complex series of collaborations and interactions.

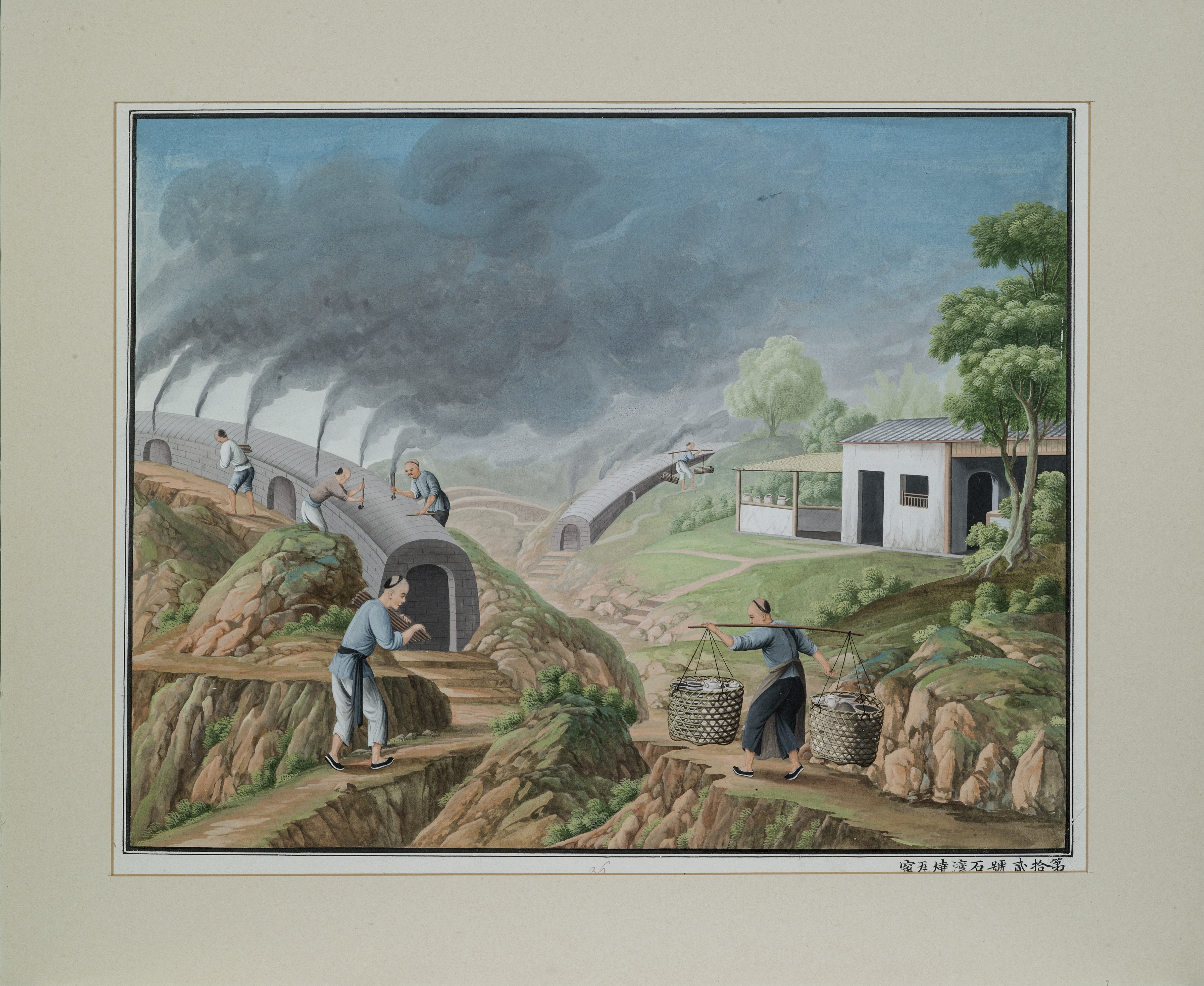

This mode of production, which resembled an early form of production line manufacturing, made it possible to produce ceramics on such a vast scale while maintaining the extremely high quality of goods demanded by the imperial court. It also made it possible to adapt the production to the sometimes-quirky demands of some emperors, who saw the production of innovative ceramics as personal prestige projects. The new shapes and designs, colours and materials entered Jingdezhen by way of the imperial kiln supervisors, who were delegated to Jingdezhen from the imperial workshops at the court, where they had access to the finest skills and technologies. But the scale of the porcelain production in Jingdezhen also came at a cost: to the workers themselves, who had to do hard manual labour under difficult conditions and often without the support network that families normally provided, because most of the workers were itinerants, who had left their homes to provide this labour, and to the environment. Mountains stripped bare to supply firewood and fern, cavities in the hillsides where clay had been dug, and skies darkened by smoke from the chimneys characterised the Jingdezhen surroundings (fig. 4). The locals paid a heavy price for the privilege of supplying the emperors and their households with fine porcelains.

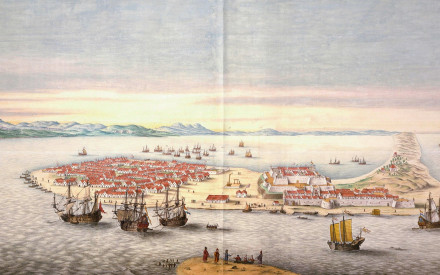

The production-line style of ceramics manufactures also made it possible to adapt the process to the increasing demands of foreign consumers. While the imperial kilns continued to produce for the demands of the emperors, a vast number of private kilns located in the wider surroundings of Jingdezhen, drew on the resources and skills of the imperial workshops to produce ceramics that catered to the demands of consumers all over the world. Jingdezhen’s blue-and-white porcelains have been found throughout Asia, the Indian Ocean world, Africa, Europe and the Americas (fig. 5). The quantity of 133,000 individual pieces ordered by the emperor in 1459 almost seems modest when compared to the millions of pieces that found their way to consumers in Europe alone. But Jingdezhen’s potters probably could never have produced so many fine pieces for consumers abroad if the emperor’s demands had not encouraged the development of large-scale production that characterised Jingdezhen for so many years.

Suggested readings

Gerritsen, Anne. The City of Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Gillette, Maris Boyd. China’s Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

Kerr, Rose, and Nigel Wood. Ceramic Technology. In Science and Civilisation in China, Vol 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part XII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Medley, Margaret. The Chinese Potter: A Practical History of Chinese Ceramics. London: Phaidon, 2006.

Scott, Rosemary E., ed. The Porcelains of Jingdezhen. London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, 1993.