Museum Prinsenhof is located in the former monastery where William of Orange took refuge in 1572 and was murdered in 1584. The museum exhibits objects linked to the Oranges and other art and historical works from Delft. The city is best known for the imitations of Chinese and Japanese porcelain produced there from the early seventeenth century onwards. Besides examples of this so-called Delft Blue, Museum Prinsenhof is home to a considerable quantity of Asian ceramics. The vast majority of this collection comes from three former collections.

Willen Jan Rust

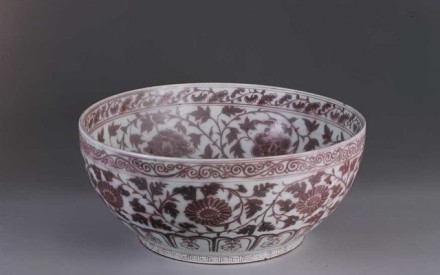

Most objects from the Asian ceramic collection were donated by Willem Jan Rust (1907–1987) to the municipality of Delft in 1971. For example, among the objects is an early seventeenth-century Chinese Kraak dish with a central decoration of a bird on a rock within a star pattern (fig. 1). A vase with a decoration of birds and exuberant flowers on a red honeycomb motif was made slightly later (fig. 2). This decoration is typical of objects from the Shunzhi period (1644–1661), an era that bridged the transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties. Among the Japanese ceramics is a fan-shaped bowl made of Imari porcelain, which is painted with the ribs of a fan and cherry blossoms (fig. 3). The collection of the Jan Menze van Diepen Foundation has a similar example, which probably formed a set with bowls like the one in Museum Prinsenhof. An example of nineteenth century Asian ceramic is a Chinese plate from the Guangxu period (1875–1908) with a decoration of baihuadi, or ‘one hundred flowers’ (fig. 4). This type of decoration originated during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1736–1795), but remained popular deep into the nineteenth century.

Huis Lambert van Meerten

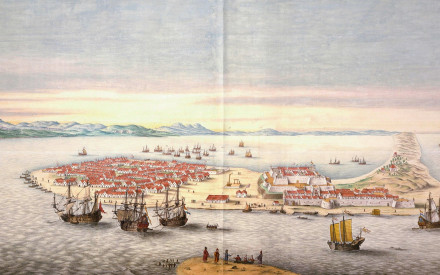

For several years now, Museum Prinsenhof has had Asian ceramics from the former Delft Museum Lambert van Meerten on long-term loan from the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands. From 1893, Van Meerten (1842-1904) exhibited his collection in a purpose-built neo-Renaissance-style house on Oude Delft, a canal in the city. Van Meerten’s collection was sold when he went bankrupt in 1902. The house was preserved through the establishment of a foundation, which transferred it to the state in 1907. Rijksmuseum Huis Lambert van Meerten opened as a museum in 1909 and continued to acquire Asian ceramics. After the museum’s closure in 2013 a large part of the collection was given on long-term loan to Museum Prinsenhof Delft including almost 200 Asian ceramic objects, such as Chinese Kangxi porcelain (fig. 5), and eighteenth-century Imari porcelain from Japan (fig. 6).

Museum Nusantara

The museum collection also includes Asian ceramics from the former Museum Nusantara. This museum, with a focus on Indonesian culture and history, was a continuation of the Ethnographic Museum founded in 1911, which was based at the Prinsenhof. The Ethnographic Museum arose from the collection of the Indische Instelling, a former training institute for colonial administrative officials in Delft. The core collection consisted mainly of donations by former students and colonial officials from the institute. Over the years, Museum Nusantara gradually developed a more active acquisition policy. When the museum closed its doors in 2013 objects were selected to be added to the Museum Prinsenhof’s collection. These include some rare pieces of Asian ceramics, such as a Chinese stoneware medicine jar with a finely carved wooden stopper of figures (fig. 7) and a Japanese porcelain water jug with a silver mount made in Indonesia, possibly Sumatra (fig. 8). The remaining collection of Museum Nusantara has been repurposed. Currently Museum Prinsenhof is working on plan for provenance research into the objects from the former Nusantara collection.

And further…

In addition to objects from these former collections, the museum owns several other examples of Asian ceramics, such as export porcelain with a link to Delft. In the eighteenth century, the upper class in Delft, like those in other Dutch cities, ordered armorial porcelain from China. Among them was Joan Carel van Alderwerelt, who was director of Delft’s Dutch East India Company’s (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) Chamber of Commerce from 1777 to 1791. The descendants of this Delft entrepreneur donated several pieces of a tea service featuring Van Alderwerelt’s coat of arms to the museum (fig. 9).

Also visit the website of Museum Prinsenhof Delft.

Literature

D.F. Lunsingh Scheurleer, Ceramiek uit de collectie Rust, Delft: W.D. Meinema B.V., 1975.

J.L.W. van Leur, De Indische Instelling te Delft, meer dan een opleiding tot bestuursambtenaar: 125 jaar verzamelen (Delft, 1989).

Steven Braat, ‘De keramiekcollectie,’ in: Steven Braat, Jos W.L. Hilkhuijsen, and Michiel Kersten, Museum Huis Lambert van Meerten Delft, Leiden: Primavera Press, 1993, pp. 85–142.

Arnold Wentholt, Nusantara: Highlights from Museum Nusantara Delft (Leiden, 2014).

Suzanne Klüver, ‘Keramiek uit de collectie Rust: Aandacht voor een gepassioneerd verzamelaar,’ Vormen uit Vuur 225 (2014) 2, pp. 24-31.

Cat. Meer dan blauw: Topstukken uit Museum Prinsenhof, Delft: Stedelijk Museum Het Prinsenhof, 2015.