From the sixteenth century onwards, rustic, imperfect objects were considered as the quintessence of aesthetics in the Japanese tea ceremony (chanoyu).

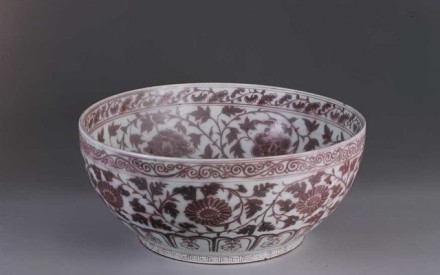

This philosophy was refined by tea master Sen no Rikyū (千利休; 1522-1591). He applied the concept of wabi, which can be loosely translated as ‘imperfect’, to every aspect of the ceremony: the environment in which it was performed, the presentation and associated objects, and the way the tea was to be made and consumed.1 Korean buncheong bowls (fig. 1), which had been made since the fifteenth century, were particularly popular for drinking tea. In Korea, these simple objects served as rice bowls for the lower classes, but in Japan they were exalted as the embodiment of the ideals of the wabicha and thus Japan’s elite culture. The first documented use of Korean bowls in a tea ceremony dates back to 15372 , and appears in the Matsuya kaiki (松屋会記), a detailed record on the organisation of the tea ceremony compiled by the Matsuya merchant family from Nara.3 The popularity of this type of bowl grew rapidly. Between 1555 and 1558 they already accounted for twenty percent of all the bowls used in chanoyu, and between 1558 and 1572 this had risen to over thirty percent.4

- 1Rumiko Handa, ‘Sen No Rikyū and the Japanese Way of Tea: Ethics and Aesthetics of the Everyday’, Interiors: Design, Architecture, Culture 4, no. 3 (2013), p. 232.

- 2Nam-lin Hur, ‘Korean Tea Bowls (Kōrai Chawan) and Japanese Wabicha: A Story of Acculturation in Premodern Northeast Asia’, Korean Studies 39, no. 1 (2015), p. 6.

- 3Eric C. Rath, ‘Reevaluating Rikyū, Kaiseki and the Origins of Japanese Cuisine’, The Journal of Japanese Studies 39, no. 1 (2013), p. 73.

- 4John Carter Covell, ‘Japan’s Deification of Korean Ceramics’, Korea Journal 19, no. 5 (1979), p. 20.

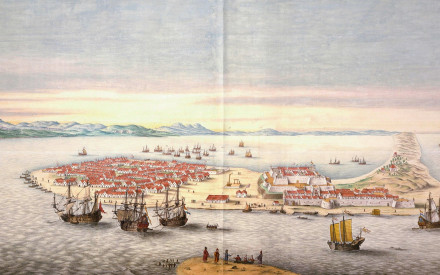

Daimyo Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉, 1536-1598, fig. 2) also had several Korean objects in his collection, his most cherished being Ido tea bowls. Hideyoshi and his troops invaded Korea at the end of the sixteenth century. Due to the appreciation for Korean ceramics in Japanese tea culture, one of Hideyoshi’s goals during these Japanese Invasions (1592-1598) was the forced relocation of skilled Korean potter families to Japan. He mobilised seven divisions of combat units supplied by different daimyo (feudal lords), and dispatched another six special units to Korea that were tasked with looting cultural goods.5 This approach by the Japanese army proved successful: many Korean potter families worked in Japan during this period to produce the much sought-after ceramics locally and also to promote Japanese ceramic production. Because of this, the Japanese Invasions are also called ‘the Ceramic Wars’ or ‘the Tea Bowl Wars’.

- 5James B. Lewis, ‘War and Cultural Exchange’, in The East Asian War, 1592-1598 (Routledge, 2015), p. 324.

Many of these Korean potters ended up in Naeshirogawa, on the island of Kyushu, which significantly increased the area’s ceramic production (fig. 3). Local rulers of the Satsuma domain were responsible for protecting the Korean potters and their work when tensions arose between Naeshirogawa and surrounding villages due to the scarcity of raw materials.6 For example, to protect the Korean potters and avoid felling too many trees that were needed as fuel for the kilns, the Nabeshima domain issued an appeal to limit the number of Japanese potters.7

Although the Korean potters were protected by local rulers in times of scarcity, restrictions were also imposed on them. For instance, they had no freedom of movement beyond the village where they had to live and work. Also, in contrast to other regions, in Satsuma the Korean community was subjected to an anti-assimilation policy.8 This meant that the Korean community in Satsuma had to remain as ‘Korean as possible’. For example, in order to protect the unique Korean way of producing ceramics, a Korean potter from Naeshirogawa was not allowed to marry outside the village’s Korean community. However, outsiders were permitted to marry into this community.9 Furthermore, the daimyo of the region encouraged the Korean communities to continue speaking the Korean language, and to observe their Korean manners and customs. Tachibana Nankei (橘南谿; 1753-1805), a physician from Kyoto, describes his visit to Naeshirogawa in the late eighteenth century as follows: ‘All these scenes seem to remind me that I am in a foreign country. I am not really in the land of Japan’.10

- 6Rebekah Clements, ‘Daimyo Processions and Satsuma’s Korean Village’, Japan Review, no. 35 (2020), p. 227

- 7Susan Broomball. ‘Shaping Family Identity Among Korean Migrant Potters in Japan During the Tokugawa Period.’ In Keeping Family in an Age of Long Distance Trade, Imperial Expansion, and Exile, 1550-1850, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020, p. 43.

- 8Soyōng Yu, ‘일본 도자기 ‘사쓰마야키’ 빚는 ‘15대 심수관’ 초청 강연’ Ilbon tojagi “sassŭmayak’I” pinnŭn “15tae Shim Sugwan” ch’och’ŏng kangyŏn (‘An invitational lecture on “The 15th Shim Soo-gwan” that makes Japanese ceramics “Satsumayaki”’), Dongpo News, 18 July 2018.

- 9Nam-lin Hur, ‘Korean Tea Bowls (Kōrai Chawan) and Japanese Wabicha, ‘A Story of Acculturation in Premodern Northeast Asia’, Korean Studies 39, no. 1 (2015), p. 9.

- 10Ibid.

Over time, the relationship between Korea and Japan somewhat normalised. In 1618, the Korean Joseon government called on all Korean potters to repatriate to their homeland, but this was met with a tepid response. The prospect of returning to the Joseon Empire was not very appealing. After the Japanese invasions, ceramic production in Korea virtually collapsed. The country was plundered; not only had the Japanese army abducted the potters, but it also seized the raw materials required to manufacture porcelain. In addition, many kilns in Korea were left in ruins.11 Because of this, the conditions for producing ceramics had deteriorated enormously. Many Korean potter families had meanwhile built a new life in Japan and enjoyed some advantages and protection from local rulers. In Naeshirogawa, the forced resettlement of Korean potters at the end of the sixteenth century is still acknowledged in several ways. The tombstones of these men and women are a short distance from the village, along with a memorial stone commemorating their story (fig. 4).

Literature

Broomhall, Susan. ‘Shaping Family Identity Among Korean Migrant Potters in Japan During the Tokugawa Period’, in Heather Dalton (ed.),Keeping Family in an Age of Long Distance Trade, Imperial Expansion, and Exile, 1550-1850, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020, pp. 29-56

Clements, Rebekah. ‘Daimyo Processions and Satsuma’s Korean Village’, Japan Review, no. 35 (2020), pp. 219-230

Covell, John Carter. ‘Japan’s Deification of Korean Ceramics’, Korea Journal 19, no. 5 (1979), pp. 19-26

Handa, Rumiko. ‘Sen No Rikyū and the Japanese Way of Tea: Ethics and Aesthetics of the Everyday’, Interiors: Design, Architecture, Culture 4, no. 3 (2013), pp. 229-247

Hur, Nam-lin. ‘Korean Tea Bowls (Kōrai Chawan) and Japanese Wabicha: A Story of Acculturation in Premodern Northeast Asia’, Korean Studies 39, no. 1 (2015), pp. 1-22

Lewis, James B. ‘War and Cultural Exchange’, in James B. Lewis (ed.), The East Asian War 1592-1598, London: Routledge, 2015, pp. 339-355

Rath, Eric C. ‘Reevaluating Rikyū: Kaiseki and the Origins of Japanese Cuisine’, The Journal of Japanese Studies 39, no. 1 (2013), pp. 67-96

Yu, Soyōng. ‘일본 도자기 ‘사쓰마야키’ 빚는 ‘15대 심수관’ 초청 강연’ Ilbon tojagi “sassŭmayak’I” pinnŭn “15tae Shim Sugwan” ch’och’ŏng kangyŏn (‘An invitational lecture on “The 15th Shim Soo-gwan” that makes Japanese ceramics “Satsumayaki”’), Dongpo News, 18 July 2018, http://www.dongponews.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=37407

- 11Susan Broomhall, op. cit., p. 44.