A significant quantity of the Asian ceramics in Museum Prinsenhof Delft was donated by the ceramics collector Willem Jan Rust (1907-1987) as part of an even larger donation. In his attempt to bring together an overview of two thousand years of global ceramic history, Rust collected widely and on a large scale. This means that it is possible to compare Asian ceramic objects in his collection with each other and with other types of ceramics in the same collection.

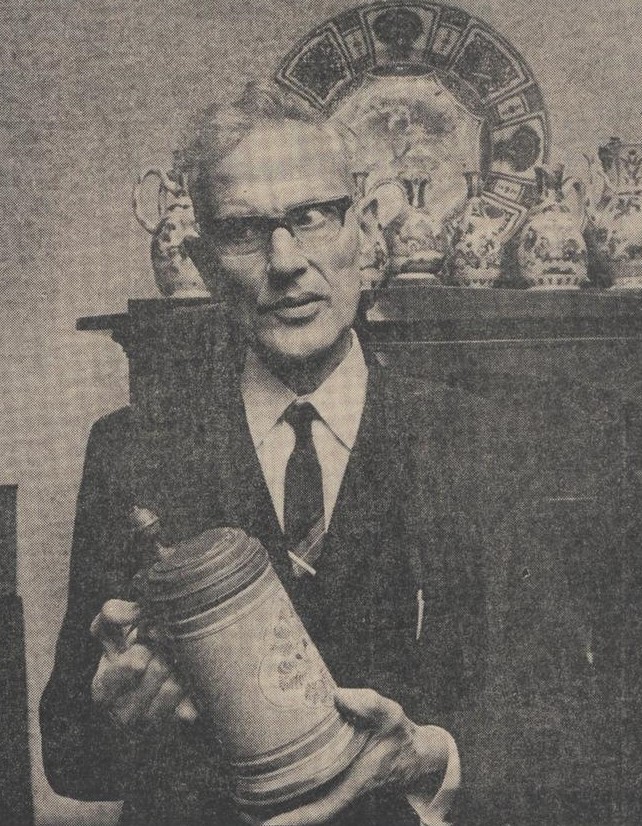

The collector

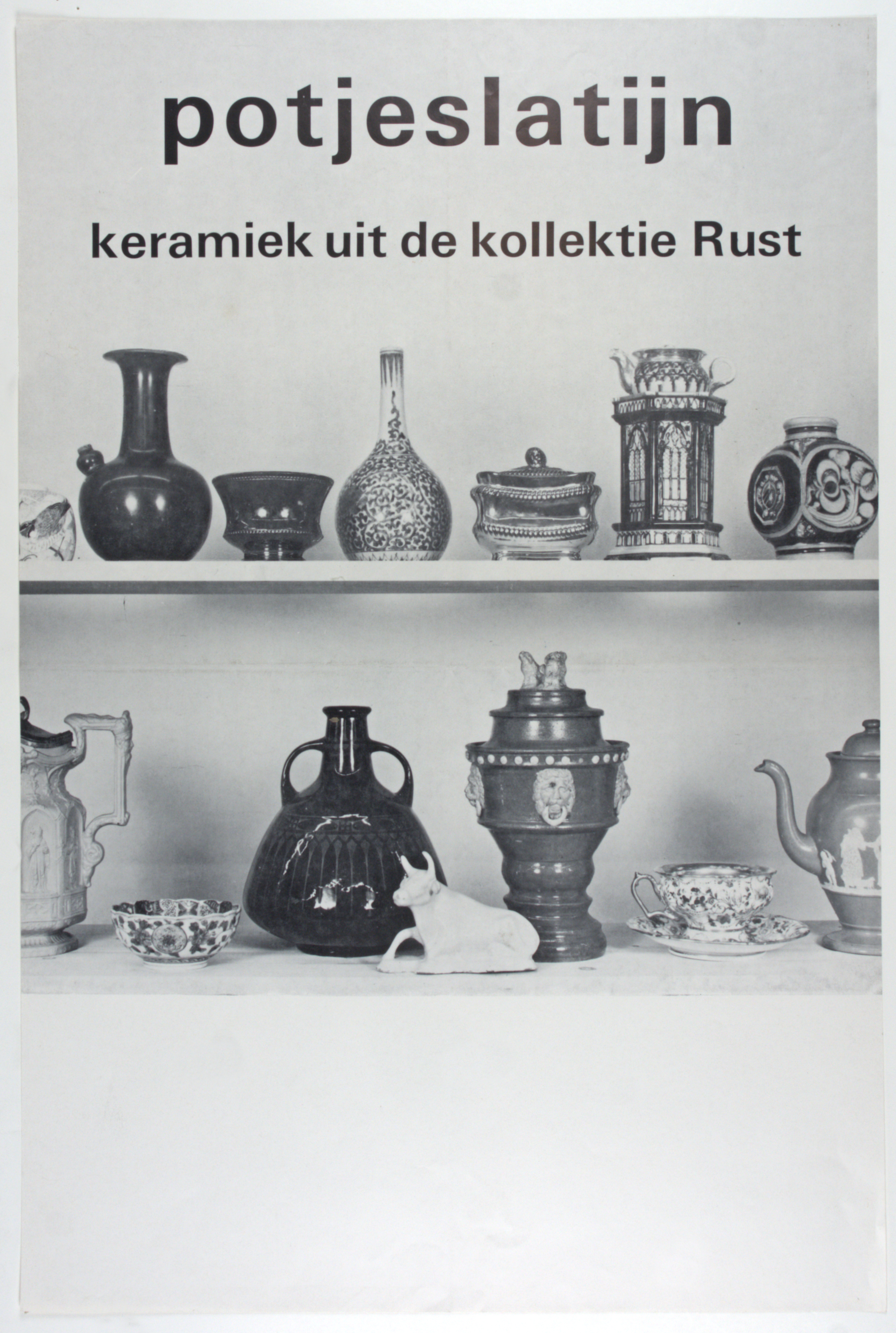

Willem Jan Rust (fig. 1) was a devotee and connoisseur of archaeology, glass and ceramics. In 1934, he became the first curator of the Goois Museum in Hilversum, today’s Museum Hilversum. In 1952, his book Nederlands porselein (Dutch porcelain) was published to accompany an exhibition of the same name at Museum Willet Holthuysen in Amsterdam, which, when reprinted in 1978, was provided with a highly complimentary foreword by D.F. Lunsingh Scheurleer, former government inspector of movable monuments and also a ceramics specialist. In 1975-1976, Lunsingh Scheurleer organised the travelling exhibition Potjeslatijn, which featured 200 ceramic objects from the Rust Collection. These included Chinese and Japanese porcelains (fig. 2), such as a fan-shaped dish (fig. 3).

The character of the collection

Rust amassed a collection of over 3,000 ceramic objects. Apart from Chinese and Japanese porcelain, he collected European majolica, stoneware and faience as well as Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Peruvian earthenware, with the intention of compiling a reference collection. About this, he said, “Of course there are also substantial gaps in it. But it is a foundation, an overview on which you can build.”

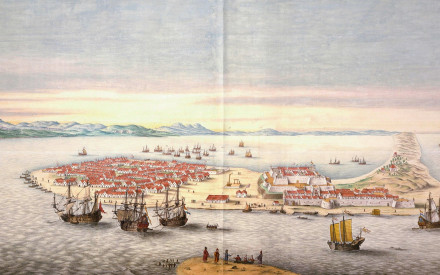

Perhaps because of the scope and size of his collection, Rust had trouble finding a museum willing to accept it as a donation. He offered it to the municipality of Amsterdam in 1970, which was uninterested. Other places also refused – Rust said he became desperate. In 1971, the collection finally found a home at Museum Prinsenhof in Delft. However, since then the overview of ceramics history that Rust assembled has not been expanded on, as Museum Prinsenhof concentrates on Delftware and the Asian ceramics it imitates. The vast majority of Rust’s collection is therefore not on display. Objects that are shown include a Chinese Kraak dish (fig. 4) with a central medallion depicting a bird on a rock, as well as a Delft earthenware plate with a similar decoration (fig. 5). This is just one example which confirms that Delft painters used Chinese porcelain as examples when decorating their earthenware.

Highlights of the collection

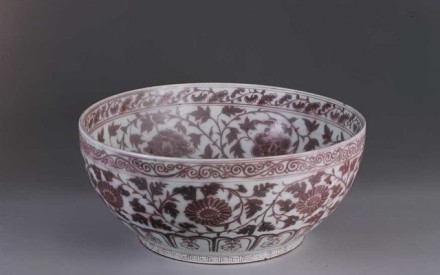

Rust opted primarily for both diversity and quantity in his collection in order to provide a more representative overview of overall ceramic production than collections that focused on the top end of the market. For example, there is a relatively large number of common Kraak and blue-and-white porcelains from the Kangxi period (1662-1722) among the Asian ceramic objects in the Rust Collection. This is not to say that there are no high-quality and rare Asian among his objects. A fine example is a vase (fig. 6) with a decoration of birds and flowers on a red honeycomb motif from the Shunzhi period (1644-1661). This period represented a transition between the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, and porcelain produced during it is relatively rare in European collections.

One of Rust’s special interests was Amsterdams Bont, Asian porcelain with a blue-and-white decoration that was augmented in the Netherlands using a variety of colours as well as gold. In 1965, he published an article on the subject in the Mededelingenblad of the Dutch Society of Friends of Ceramics and Glass, in which he discussed some examples of Amsterdam Bont in his collection. These included a klapmuts bowl with additional decorations of flowers and figures in red and gold (fig. 7), which Rust says can be dated to the second quarter of the eighteenth century, making it ‘possibly one of the earliest expressions of Amsterdam Bont’. Due to the diversity of Rust’s objects, this bowl can be contrasted with a less well-painted – but no less interesting – ginger pot from his collection, which was completely repainted with dragons in a ‘landscape’ of flowers, plants, ships and rivers (fig. 8).

Conclusion

Although only a limited number of pieces from the Rust Collection are on display, the collection is of great value to Museum Prinsenhof Delft because its scope enables connections to be made between ceramic production in different places and for different market segments. More research into this striking collector, his collecting practice, and the provenance of objects in his collection is therefore desirable.

Literature

Willem Jan Rust, Nederlands porselein (Amsterdam, 1952).

Willem Jan Rust, ‘Een classificatie van Amsterdam bont,’ Mededelingenblad Nederlandse Vereniging van Vrienden van Ceramiek en Glas 41 (1965), pp. 9-21.

Toon van Severen, ‘Verzameling te geef: Het trieste lot van een aardewerk-minnaar,’ Het Parool 31 July 1970, p. 15.

D.F. Lunsingh Scheurleer, Ceramiek uit de collectie Rust (Delft, 1975).

Suzanne Klüver, ‘Keramiek uit de collectie Rust: Aandacht voor een gepassioneerd verzamelaar,’ Vormen uit Vuur 225 (2014) 2, pp. 24-31.