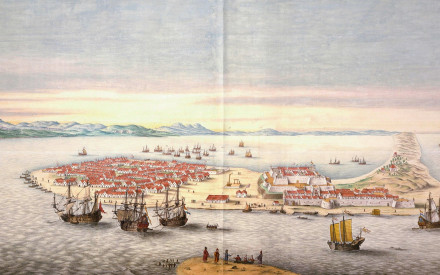

The first porcelain received by the Rijksmuseum – or rather its immediate predecessor, the Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden (Royal Cabinet of Rarities) – came from the collector Jean Theodore Royer, who lived in The Hague. Royer, a lawyer, devoted his spare time to studying the Chinese language and collecting Chinese objects. His efforts are an interesting and early example of a serious study of China. In the 1770s he compiled long lists of words that were to form the basis for a Chinese dictionary, and through friends who worked for the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC), he corresponded with at least two Chinese who helped him study the language and collect objects. Royer was interested in the objects that cultured and educated upper-class men (the so-called literati) surrounded themselves with. This way, he would be able to better understand his Chinese counterparts. His collection has largely been preserved and is now housed in the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

The importance of the Chinese objects was linked to the fact that they came directly from China – this made them trustworthy sources of knowledge. This was in contrast to the many publications on China, which were mostly based on the reports of the Jesuit missionaries who had been trying to spread Christianity in China since the 16th century. Such information was therefore biased and second-hand.

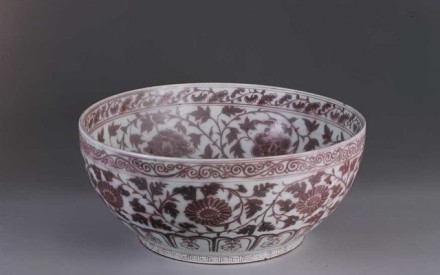

In addition to this early ‘ethnographic’ collection, Royer also had a large collection of about 1,000 Chinese and Japanese porcelain objects, most of which were not new and not directly from China. The vast majority were Transitional porcelains (c. 1635-1650, fig. 1), Kangxi porcelains (c. 1685-1722, fig. 2), or Japanese Kakiemon porcelains from c. 1700 (fig. 3): porcelain from the halcyon days of the VOC, when the Netherlands was the prime location for dealers from all over Europe to buy porcelain.

Royer was a distant relative of Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687), who was secretary to the princes of Orange, a gifted musician and poet and a champion of good taste. Constantijn Huygens had five children, but few grandchildren. In 1785, all of his property belonged to his great-granddaughter Susanna Louise (1714-1785). She lived in the large town house that Constantijn had built to a design by himself and the well-known architects and artists Jacob van Campen (1596-1657) and Pieter Post (1608-1669). The documents from the settlement of Susanna’s estate record that Royer paid a considerable sum for the porcelain he purchased from her legacy. The pieces would certainly have been important to Royer as examples of Chinese and Japanese ceramics, but the Huygens association would undoubtedly have played a role as well. From 1786 onwards, Royer had a genuine porcelain room on the first floor of his house on the Herengracht in The Hague. It was a large room, with painted Chinese wallpaper on the walls depicting the various stages of porcelain production. The porcelain was displayed on corner pyramids and tables, leaving the painted wallpaper largely visible.

While we know that Royer had a large collection of porcelain, much of which came from his distant cousin Susanna Louise Huygens, it is unfortunately not absolutely clear which pieces this concerns. In 1814, Royer’s widow Johanna Louise van Oldenbarneveld Tullingh bequeathed the collection to William of Orange, who would shortly afterwards reign as King William I. He installed the collection in the Royal Cabinet of Rarities. It was not until 1876 that the objects were numbered and recorded in an inventory for the first time: the vast majority of the porcelain registered that year was Royer’s, but pieces may have been added to the collection between 1814 and 1876. When researching the acquisitions by the Royal Cabinet of Rarities, it transpired that the records were not always well maintained during those years, so it cannot be precisely determined which – if any – porcelain was added to the Royer Collection between 1814 and 1876. And that is a pity, because it means that the Royer pieces are untrustworthy benchmarks for dating other porcelains.

Literature

Jan van Campen, Collecting China. Jean Theodore Royer (1737-1807), Collections and Chinese Studies, Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2021.