The core part of the East Asian porcelain holdings from the Porzellansammlung (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden) today (fig. 1), stems from the legendary former eighteenth century royal collection.

The then Elector of Saxony (1696 – 1733) and King of Poland (1697 – 1706 and 1709 – 1733), Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) (fig.2), is possibly best known for his insatiable appetite for porcelain. According to his own statement, he once described his passionate interest as a particularly strong and incurable sickness, the so-called ‘maladie de porcelaine’. However, it was not only the king's enthusiasm for the coveted East Asian material, but in particular his keen economic interest that made Saxony the birthplace of European porcelain. In 1710, the royal manufactory was officially founded in the town of Meissen, fifteen miles upriver from the Saxon capital city of Dresden.

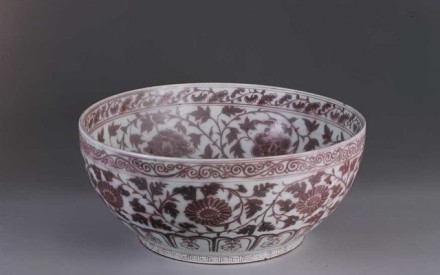

Already during the early eighteenth century, Augustus the Strong’s collection of Chinese and Japanese porcelain was regarded as the largest in Europe. To acquire the best items available in this geographical region, he not only used his political influence, but also immense financial resources: between around 1715 and at least until 1727 – in less than 18 years – the Elector-King had amassed around 25,000 pieces of East Asian porcelain. The purchased porcelain derived from varying sources and in general Augustus the Strong did not aim for single pieces or small quantities, but rather whole collections through the offices of his ministers, from several dealers, the Polish Voivode Chemetowski or even from his ex-mistress Countess Teschen. In the end, this impressive number had reached over 29.000 items. Most of his collection dates to the latter part of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century and showcases primarily contemporary objects, such as Chinese Kangxi (fig. 3-4), Japanese Imari (fig. 5) and Kakiemon porcelain (fig. 6).

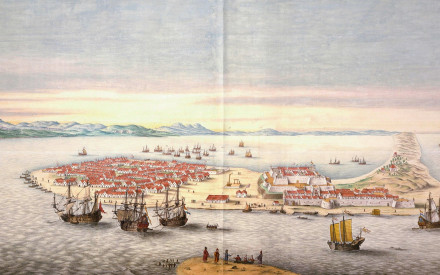

In 1717 Augustus the Strong had purchased the Holländische or so-called Dutch Palace, located on the bank of the River Elbe in Dresden, to display his extensive East Asian porcelain treasures and in particular his own Meissen porcelain ware. An excellent recording that was made during the 1720s, documented all pieces on display. Hereby the inventory numbers and chapter ciphers - or so-called Palace Numbers - were painted onto or incised into the porcelain body (fig. 7). Until today, this way of registration allows to relate most of the extant pieces in the Porzellansammlung with their respective inventory entries. It thus offers not only a tool for dating pieces but gives a comprehensive insight into the trade, taste, collecting and display strategies of luxury commodities like East Asian porcelain during the eighteenth century.

From the initially around 29,000 Chinese and Japanese ceramic objects, more than 8,000 are still extant in the Porzellansammlung today, which, in combination with the preserved archival documents, make this unique collection one of the world’s largest and most important East Asian reference collections from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Since 2014 this rich material has been thoroughly photographed, assessed and researched for the first time. The collection is catalogued in its entirety by a group of more than thirty-five renowned international senior and junior experts in the field of Chinese and Japanese ceramics under the academic supervision of Prof. Dr. Christiaan Jörg.

An innovative, open access digital platform ‘The Royal Dresden Porcelain Collection’ has been developed to showcase the entire reference collection, the extensive archival material and the network of information between both. Over forty essays and introductory texts on the various Chinese and Japanese porcelain groups will provide insight into the historical background of collecting porcelain at the Dresden court. The interconnectedness of the different materials allows not only for an explorative approach, but also for an ongoing contextualization in different, curated narratives. This novel and aesthetically ambitious presentation of the objects will inspire our professional and general readers alike. The launch of the website is scheduled for 2023.

Click here for some additional insights into the project.

Literature

Ruth Sonja Simonis, Microstructures of global trade, Porcelain acquisitions through private trade networks for Augustus the Strong, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2020.

Randhahn, Karolin. "Die Porzellansammlung Dresden. Zu den Verkäufen des historischen Bestandes bis 1920," Ostasiatische Zeitschrift 40 (Herbst 2020), 42–57.

Stefan Herzig, Kristina Friedrichs and Heinrich Karge, Das Japanische Palais in Dresden Porzellanschloss ,Staatsmonument, Museum. Konzeption und Baugeschichte, Petersberg 2019.

Julia Weber, Copying and Competition. Meissen Porcelain and the Saxon Triumph over the Emperor of China, in: The Transformative Power of the Copy, a Transcultural and Interdisciplinary Approach, Heidelberg Studies on Transculturality, Heidelberg, 2017

Ulrich Pietsch and Cordula Bischoff, Japanisches Palais zu Dresden. Die Königliche Porzellansammlung August des Starken, Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2014.

Cora Würmell, Japanese Porcelain from the Royal Collection, The Porzellansammlung Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, in: Arts of Asia, Vol. 44, Issue 4, July-August 2014.

Eva Ströber, La maladie de porcelaine ,ostasiatisches Porzellan aus der Sammlung Augusts des Starken, Leipzig 2001.