Japan already had a long and rich history of ceramic production before the country started manufacturing porcelain. The earliest examples date back thousands of years before the beginning of our European era, but large-scale production did not begin until the Kamakura period (1192-1333), when a ceramics industry emerged in Seto, now Aichi Prefecture.

The influence of tea masters increased along with the rise of tea culture and the growing importance of the related ceremony (chanoyu). They carefully selected the objects to be used, admired and discussed during the tea ceremony and also fulfilled the role of merchant. During the sixteenth century, Korean ceramics, their irregular shapes and rough surfaces sharply contrasting with Chinese porcelain, became highly prized, to such an extent that during the Japanese Invasions (1592-1598) Korean potter families were brought to Japan as prisoners of war to manufacture such objects on Japanese soil (see The Korean Potters in Japan). Both the emerging tea culture and the arrival of the Korean potters had a major impact on the development of Japanese ceramics. Seto, Karatsu, Bizen and Kyoto are among the most important stoneware-manufacturing regions (fig. 1).

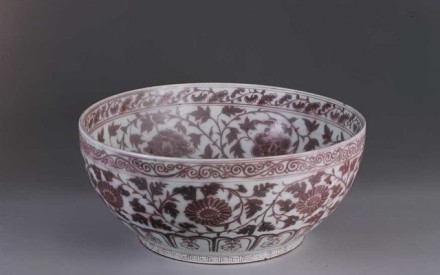

Porcelain was first produced in Japan at the beginning of the Edo period (1603-1867) in and around the city of Arita, now Saga Prefecture, near the city of Karatsu, where many of the Korean potters had settled. Porcelain clay was found in this region, which, combined with the Korean potters’ expertise, enabled the manufacture of porcelain. This early Japanese porcelain is known as shoki-Imari (Early Imari), named for the port from which the pieces were shipped. It was produced for the domestic market, hence its scarcity in Dutch collections. The decorations are mainly in underglaze cobalt blue, and were inspired by Chinese examples or have their own, Japanese character (fig. 2). It didn’t take long before potters were also making porcelain with celadon, cobalt and iron glazes. Early pieces are characterised by a small footring, an expressive decoration and a fairly thick glaze.

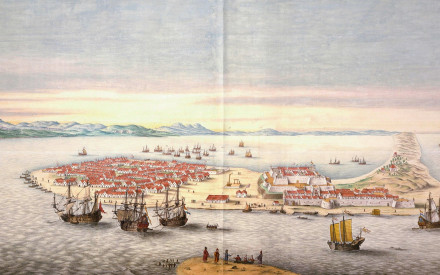

The development and export of Japanese porcelain, already underway for some time within the inter-Asian market, received a boost due to domestic unrest in China during the transition from the Ming to the Qing dynasties (1368-1644 and 1644-1912, respectively). Starting in the 1640s, the Japanese colour palette was enriched with overglaze enamels, a technique introduced by Chinese potters fleeing the turmoil in their own country. The Dutch trade in Chinese porcelain was also greatly impeded as a result of this civil war. By now, porcelain products from Japan were well known and were a good alternative, so from the mid-seventeenth century the Dutch compensated for the unavailable Chinese merchandise by purchasing substantial amounts of Japanese products through the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) and private trade.

Porcelain with blue-and-white decorations remained popular and was produced on a large scale. Ongoing advances in the Japanese industry meant that exceptional porcelain could be made from the second half of the seventeenth century. At the outset, fairly light enamel colours were used on shoki-Imari, while thicker, brighter colours were applied to Kutani ware. The former soon developed into finer, more translucent enamels, as seen on the high-quality Kakiemon porcelain from Nangawara, which is distinguished by a milky-white body covered with a thin glaze with a silky sheen (fig. 3). Porcelain from Nabeshima is a high point: under the leadership of the clan of the same name, exceptionally refined porcelain was produced exclusively for use by the shogunate in Japan (fig. 4).

Objects with coloured decorations eventually became popular in Europe. Japanese porcelain known in Europe as Imari, with an underglaze-blue decoration and mostly red, green, gold and black enamels, was widely exported in the second half of the seventeenth and during the eighteenth century.

The opening up of Japan at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868-1912) meant an influx of foreign technology and knowledge but, at the same time, imposed a considerable burden on Japan’s rapidly changing society, including traditional production processes. The elimination of the broad ruling class of daimyo and samurai families resulted in a gap in the potters’ sales market. Stimulated by the new government, the export market was seen as the solution. High-quality ceramic pieces were presented at numerous world exhibitions, fuelling the European and North American fascination with these ‘exotic’ Japanese objects. Among the most popular was Satsuma ware, a cream-coloured pottery that was richly decorated according to foreign taste with colourful decorations and plentiful gold (fig. 5). A more restrained example is Hirado porcelain, which had been produced in Mikawachi since the eighteenth century. The snow-white body is typically decorated in blue-and-white with or without relief decorations. The far-reaching changes brought about during the Meiji period also enabled potters to develop a personal style, with accompanying individual fame. An example of this is the potter Miyagawa Kozan (1842-1916).

Literature

Complete catalogue of Shibata collection, The Kyushu Ceramic Museum, 2019

Fitski, M., Kakiemon Porcelain: a Handbook, Leiden: Leiden University Press; Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2011

Impey, O., The early porcelain kilns of Japan: Arita in the first half of the seventeenth century, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995

Impey, O., Japanese export porcelain: catalogue of the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Leiden: Hotei Publ., 2002

Jahn, G., Meiji ceramics: the art of Japanese export porcelain and satsuma ware 1868-1912, Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2004

Jörg, J.A., Fine & Curious. Japanese Export Porcelain in Dutch Collections, Leiden: Hotei Publ., 2003

Jones, M. en Cort, L.A. (Eds.), Ceramics and modernity in Japan, Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2020