Europeans fell under the spell of Asian porcelain after it was introduced to the West in the sixteenth century, and sovereigns and other wealthy citizens surrounded themselves with this wondrous ‘white gold’. Attempts to unravel the formula failed and alchemists pursued this quest with as much fervour as they did the philosopher’s stone.

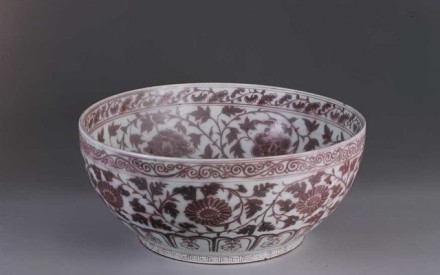

The Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, Augustus the Strong (1670-1733), one of the most well-known and passionate collectors of Asian porcelain at the time, managed to amass a collection of no less than 30,000 pieces of Chinese and Japanese porcelain during his lifetime. A transaction that took place in 1717 is a good illustration of his possibly pathological urge to collect, which he himself diagnosed as ‘la Maladie de porcelaine’. In exchange for an entire regiment of soldiers, Augustus the Strong received 151 pieces of porcelain from Frederick William I of Prussia (1688-1740), including sixteen large vases. Not surprisingly, it was at the court of Augustus the Strong that the formula for European porcelain was eventually discovered by Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682-1719) and Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus (1651-1708). Initially, red-firing stoneware (fig. 1) was produced. With the development of a formula that included the essential raw material kaolin clay, the first real formula for European hard porcelain (fig. 2) followed in 1709, a product that was manufactured in Meissen from 1710 onwards.

The first products manufactured by the Meissen factory did not differ greatly from the much-loved examples from Asia in terms of design. For example, Böttger stoneware pieces were developed that bear a strong resemblance to Yixing stoneware. In 1720, Johann Gregorius Höroldt (1696-1775) was appointed director of the Königlichen Porzellan-Manufaktur in Meissen, and during his tenure, much of the factory’s porcelain was decorated with chinoiserie representations. The extensive coffee services, vases, cups and saucers and other products that emerged from the kilns not only ended up in Augustus the Strong’s private collection, but were also distributed as diplomatic gifts to royalty across Europe (fig. 3). Meissen soon departed from the Asian examples and, under the leadership of sculptor Johann Joachim Kändler (1706-1775), the factory also specialised in making sculptures, including the most exquisite animal figures (fig. 4). Life-size parrots, lions and other animals make up a veritable menagerie of porcelain in the Japanese Palace in Dresden. Until the 1750s, products developed in Meissen dominated European taste in porcelain.

Not long after the breakthrough in Dresden, porcelain factories sprang up all over Europe. The first of these was in Vienna. One of the employees at the Meissen factory defected and shared the formula with the founder of the Vienna factory, Claude Innocent Du Paquier (1679-1751). The Viennese factory’s products (fig. 5) are very similar to those of the Meissen factory. There was also plenty of experimentation in France. The factories in St. Cloud, Chantilly and Vincennes focused on making so-called soft porcelain in the style of Asian examples, such as the highly sought-after Japanese Kakiemon porcelain, as well as products from the Meissen factory. The Vincennes factory fell under royal patronage, and after Louis XV (1710-1774) also purchased a sizeable holding, it moved to the strategically well-located Sèvres (on the Seine and on the route between Paris and Versailles). Sèvres is also where the formula for hard porcelain was eventually discovered, and under the watchful eye of Louis XV’s famous mistress Madame de Pompadour (1721-1764), the factory developed an individual style in line with the then-popular Rococo.

It produced the most astonishing and decadent objects(fig. 6), from vases with handles shaped as beautifully detailed elephant heads to candelabras with a reservoir for potpourri. Whereas Meissen had previously been the primary inspiration in the field of European porcelain, Sèvres fulfilled that role from the second half of the eighteenth century. Meanwhile, the number of porcelain factories kept increasing and were established all over Europe, often under royal patronage, but certainly not always. In the Netherlands, too, a total of five factories were established from 1759 onwards in Weesp, Loosdrecht, The Hague, Ouder-Amstel and Nieuwer-Amstel (fig. 7-9). However, the manufacture of Dutch porcelain was short-lived and the last factory closed its doors in 1814.

Due to industrialisation, porcelain could be produced on an increasingly larger scale and the target group that could afford an entire service or even several services grew rapidly. From the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in the countries with a local supply of kaolin clay, such as Germany and the Czech Republic, a large industry arose with hundreds of production facilities.