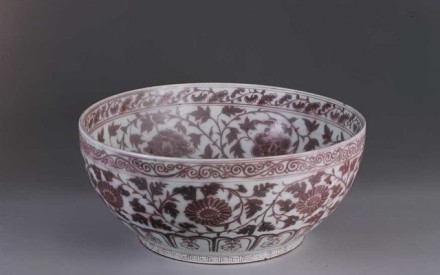

Transitional porcelain owes its name to the transitional period between the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing dynasties (1644-1912) in the mid-seventeenth century. Officially, the Qing dynasty started in 1644, but the time of unrest, struggle and rebellion lasted from about 1620 to about 1685. Despite this turbulent period, the seventeenth century was a dynamic time for porcelain producers in the Chinese city of Jingdezhen. The imperial kilns – the workshops that fulfilled the court’s substantial orders – still played an important role at the beginning of the century, but this ended in 1608. The Ming dynasty was in decline and the imperial court could no longer afford large porcelain orders. As a result, a large number of skilled potters and porcelain painters sought employment with the private manufacturers who worked for both the domestic and foreign markets.

The domestic market grew. Wealthy merchants eagerly adopted the lifestyle of the administrators-literati, traditionally the class held in the highest regard and the arbiters of good taste. This included a love of porcelain, which at this time – perhaps under the influence of the newly-arrived merchants – also had underglaze-blue decorations, often with scenes from well-known stories and inscriptions. The porcelain that was made for these customers was of a high quality, both in terms of body and glaze and in terms of the painting in beautiful, richly variegated shades of blue. The potters and painters who no longer had to work for the court felt free to produce new shapes and decorations for their new clientele. Many of these representations were based on woodcut illustrations from literary works, which were now available on a relatively large scale. The narrative depictions were often accompanied by an inscription (fig. 1). The potters had even more freedom when it came to the pieces exported to Japan, as unusual shapes and free brushwork were especially appreciated there (fig 2).

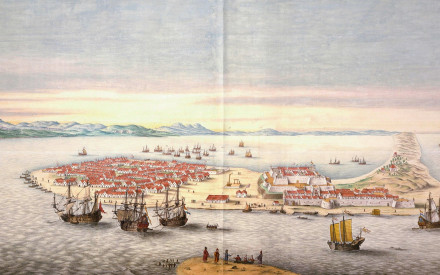

This new porcelain later became known in Western literature as Transitional porcelain. Although it was initially made for the Chinese market, it also ended up in the Netherlands, but only much later. After various conflicts with China to enforce access to trade, the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) managed to set up a trading post on Taiwan (Formosa), close to China, in 1624. Here Chinese junks brought goods, destined both for the VOC’s inter-Asian trade (especially silk for Japan) and for the VOC’s return ships to the Netherlands, of which porcelain formed a significant part. The Southern Chinese traders mainly supplied Kraak porcelain (primarily for export), but the VOC records show that the Dutch also realised that something new and refined was being made in China. Trade in the South China Sea was controlled by a network of Chinese traders led by the Zheng family. Time and again, these Chinese contacts were asked to supply this new porcelain. This finally happened in 1635, when it apparently became interesting enough for them to supply it.

Broadly speaking, the same Transitional porcelain that was sold in China was also delivered to Formosa from where it was distributed around the world. However, Chinese customers were more discerning than European merchants; moreover, the latter did their utmost to pay the lowest possible prices. This must have resulted in a difference in quality and exclusivity between what the Chinese merchants offered in Taiwan and what remained in China. Moreover, there are more inscribed pieces in Chinese collections than in (old) European collections – this also denotes a slight difference in the assortments for the domestic and foreign markets. The pieces with European shapes form a special group. They were primarily made after European pewter and silver tableware, such as beer mugs, jugs, salts, and candlesticks. From 1635 onwards, VOC officials and porcelain dealers succeeded in sending wooden models which the Chinese potters copied exactly. These pieces with European shapes were made especially for export, but were decorated with representations typical of Transitional porcelain (fig. 3). A letter written in 1635 by the VOC directors to their employees on Formosa specifies which decorations were desirable and which were not. European flowers did not sell, but Chinese representations did: ‘painted curiously and skilfully, with Chinese people on foot and on horseback, water, landscapes, pleasure-houses, their boats, birds and animals […]’.

The rolwagen, a cylindrical vase with a wide mouth, is a very common Transitional porcelain shape (fig. 4). This is a Chinese form that originated in this period. Its straight sides and large surface area lend themselves well to the refined painting for which this period is famous. Rolwagens were also popular in the Netherlands and – as is evident from estate inventories – were expensive. The narrative representations on Transitional porcelain also inspired Dutch potters: the decorations on many Delftware objects reference them.

Literature

Richard Kilburn, Transitional wares and their forerunners [± 1500-1680], Hong Kong 1981

Stephen Little, Chinese ceramics of the transitional period: 1620-1683, New York 1683

Michael Butler, Margaret Medley, Stephen Little, Seventeenth-century Chinese porcelain from the Butler family collection, Alexandria, 1990

Cynthia Viallé, ‘The records of the VOC concerning the trade in Chinese and Japanese porcelain between 1634 and 1661’ Aziatische Kunst 22/3 (1992), pp. 7-34.

Julia B. Curtis; with an essay by Stephen Little, Chinese porcelains of the seventeenth century: landscapes, scholar's motifs and narratives, New York, 1995

Michael Butler, Julia B. Curtis, Stephen Little; with essays by Qianshen Bai, Yibin Ni, Evelyn S. Rawski, Treasures from an unknown reign: Shunzhi porcelain 1644-1661, Alexandria, 2002

Dawn Odell, ‘Porcelain, Print Culture and Mercantile Aesthetics’, in The Cultural Aesthetics of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain, eds A. Cavanaugh and M. E. Yonan (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), pp. 141–158

Teresa Canepa, Jingdezhen to the world: the Lurie collection of Chinese export porcelain from the late Ming dynasty, London, 2019

Teresa Canepa and Katharine Butler, Leaping the dragon gate: the Sir Michael Butler collection of seventeenth-century Chinese porcelain, Londen, 2021

Willemijn van Noord, ‘Between script and ornament: Delftware decorated with pseudo-Chinese characters, 1660-1720,’ Journal of Design History 34 (1), 2021, pp. 1-20