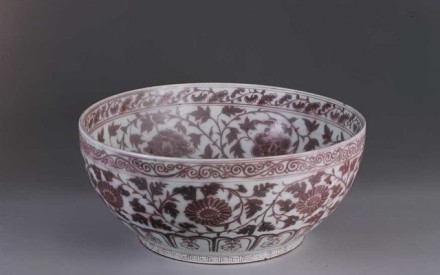

The very first time I saw this punch bowl (fig. 1) at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, I did not understand its context or how it had been created. This is because the punch bowl was made in two different locations, from two different materials with corresponding techniques, and the time that elapsed between the manufacture of the Kangxi-period porcelain covered bowl (1661-1722) and the application of the silver mounts is almost two centuries.

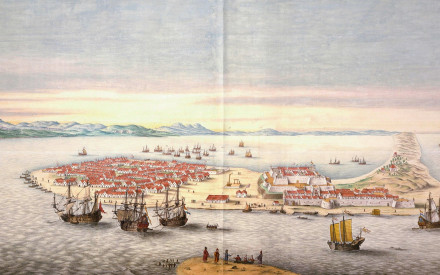

I was fascinated – possibly because it resonated with my own Chinese/Dutch background – and wondered how two worlds, two different materials, and two different periods could have united in a single object.1 In Europe, the tradition of mounting objects dates back to the eleventh century. For example, in the ecclesiastical context, ‘exotic’ materials, as well as relics, were mounted to emphasise their preciousness. The earliest documented Chinese porcelain vase in Europe – the so-called Gaignières-Fonthill vase – was once also enveloped in a mount. This Yuan-dynasty (1279-1368) qingbai vase can be traced back to the collection of Louis I of Hungary (1326-1382).2 There were no direct trade routes between Europe and China at the time, porcelain captured the imagination, and the material was an enigma. Before Europeans sailed towards Asia at the beginning of the sixteenth century, individual objects made of porcelain came to Europe from China via indirect overland routes. Mounted objects were also displayed in so-called Cabinets of Curiosities from the sixteenth century onwards. Objects of exotic and/or unknown origin, such as narwhal horns, coconuts, Nautilus shells and Chinese porcelain, were systematically collected and exhibited. Cabinets of Curiosities represented the fascinating but often unknown wider world, which the collector thus sought to possess, understand and control. The application of (gilt) silver frames emphasised their owner’s worldliness (fig. 2).3

- 1This essay is based on my MA thesis ‘Porcelain with Silver – The Revival of Mounting Chinese Porcelain in the Nineteenth-Century Netherlands’ (Leiden University, 2021). For this thesis, an inventory was made of Chinese porcelain with silver mounts from twelve museum collections and one private collection. In addition, the accounts of the firm As. Bonebakker and silversmith Jacob Helweg in Amsterdam's City Archive were frequently consulted.

- 2The mounts of the Gaignières-Fonthill vase were removed over time. The vase has been in the National Museum of Ireland’s collection since 1882, inv. no. 1882.3941.

- 3For the Von Manderscheid drinking cup, once displayed in the Cabinet of Curiosities of Duke Eberhard von Manderscheid-Blankenheim (1642-1608/10), see inv. no. M.16-1970 in the V&A’s collection.

Objects with mounts were exhibited in the context of Cabinets of Curiosities. Utility wares were also embellished with mounts, especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Adding mounts made of precious metals to these exotic objects – which included Chinese porcelain – enhanced the value of the object. Its appearance and rarity were thus literally ennobled. In addition, these same mounts served to appropriate the objects and transform them into useful and understandable pieces, such as a porcelain dish and bowl that were converted into a covered bowl by adding a mount (fig. 3). With the mass imports of porcelain from China and Japan and the development of porcelain in Europe at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the distinctiveness of Asian porcelain waned over time and with it the practice of mounting the objects.1

In the Netherlands, mounting Chinese – mainly blue-and-white – porcelain with silver underwent a revival in the nineteenth century. Interestingly, the porcelain itself did not date from that century: most of it was made during the reign of Emperor Kangxi, almost two centuries earlier, and was chosen because it mainly consisted of stand-alone objects such as vases, plates and bowls. This was in contrast to the kind of porcelain the VOC brought from China in subsequent periods: complete sets of tableware – often made to order – for the European market, either for practical use, for decoration in a special China cabinet or to decorate a mantelpiece (fig. 4). Moreover, Kangxi porcelain was usually decorated in blue-and-white, which was preferably mounted with silver.2

- 1The formula for making porcelain was discovered in Meissen in the early 18th century by the mathematician Ehrenfield Walther von Tschirnhaus (1651-1708) and the alchemist Johann Böttger (1682-1719).

- 2For porcelain with gilt bronze mounts, see Jörg, Campen, Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, pp. 234-235, cat. nos. 266, 267 and 269.

As mentioned above, originally porcelain objects were mounted to emphasise their value and beauty, highlight the collector’s worldliness and transform unfamiliar pieces into useable objects. In the nineteenth century, porcelain was mounted for very different reasons. It was long assumed that the mounts of this period were largely fitted to conceal damage. This is partly true, but there were other reasons for adding mounts, for example, to substitute missing parts such as covers with silver replacements. In addition, mounting porcelain could change the original function of the object: from a small bottle into a cigar vase and from a dish into a tray (fig. 5). Another noteworthy category is the modest rim mountings applied to the covers of kettles and tea canisters and the spouts on jugs, kettles and teapots. These ensured that the object could be used more efficiently while still retaining its original function (fig. 6).1

Mounts were also used to commemorate special moments such as wedding anniversaries, or awarded as prizes. These objects could be made to order – for example, the objects from the Backer Collection in the Amsterdam Museum (fig. 7) and two objects with a commemorative medallion in the Groninger Museum’s collection (fig. 8) – but were also sold directly from stock, as in the case of the Rijksmuseum’s punch bowl (fig. 1).2 The porcelain to be mounted was supplied by the buyer himself or bought by the silversmith from dealers.

- 1As porcelain covers did not close tightly, cover mounts ensured that they fitted securely on the mouthrim of kettles, jugs, pots and canisters. Silver spouts enabled pouring without leaking/dripping. Today, plastic pouring spouts are available that can be slid over a spout.

- 2For objects from the Backer Collection, see Vreeken, Dekker, Goud en Zilver met Amsterdamse keuren, pp. 246-249, 257; Groninger Museum, inv. no. 1904.0172; Groninger Archives, 1031, Wicher Family, 1594-1867, no. 48.

The date stamps on the silver mounts in the inventories of twelve Dutch museum collections show that the use of mounts peaked in the mid-nineteenth century. This is substantiated by the archives of the silversmith firm As. Bonebakker & Zn. and more clearly specified in the accounts of silversmith Jacob Helweg (1798-1875). Indeed, most of the mounted objects made of Chinese porcelain were delivered by them in 1851. The Bonebakker firm, Amsterdam’s leading silver manufacturer in the nineteenth century, completed numerous prestigious commissions for King Louis Napoleon, William I, William II and Anna Paulowna, among others. Jacob Helweg was employed by Bonebakker, but also worked independently. Their well-preserved archive provides an overview of much of the work they produced in the nineteenth century. The style of the silver mounts reflected the general fashion of the nineteenth century, namely combining different neo-styles. This is evident in the work of silversmith Johannes Hendrik Schmidt (1825-1900). Some silversmiths, such as Arnoldi & Wielick (1836-1863) and Jacob Helweg, were famous for making mounts, resulting in customers placing special orders with them through jewellers.

The increase in orders from the first half of the nineteenth century demonstrates that Chinese porcelain became fashionable again during this period. This coincided with the establishment of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (1813/1815) and with it the emergence of a distinct Dutch identity. The porcelain that arrived in the Netherlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was seen as part of Dutch national history. Romantic references to the country’s illustrious history were made and seen in all arts, from fine art to applied art and (interior) architecture. The memory of the once glorious homeland encouraged nineteenth-century Dutchmen to reappraise ‘old-fashioned’ porcelain – and with it, the phenomenon of mounting Chinese porcelain with Dutch silver.

Literature

Avery, L. ‘Chinese Porcelain in English Mounts’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, vol. 2, no. 9 (May 1944), pp. 266-272.

Baarsen, R. (ed.), ‘De Lelijke Tijd’, Pronkstukken van Nederlandse interieurkunst, 1835-1895, Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. exh. cat. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, 1995.

Benthem, B.J. van, De werkmeesters van Bennewitz en Bonebakker, Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2005.

Budel, H. ‘Een Porseleinmanie in de 19e Eeuw’, Aziatische Kunst, vol. 39, no. 1 (2009), pp. 2-16.

Calcer, M. van ‘Oosters Porselein met 19e-eeuwse Nederlands Zilveren Monturen’, Aziatische Kunst, vol. 40, nr. 1 (2010) 33-38.

Fei, B.Y., Porcelain with Silver – The Revival of Mounting Chinese Porcelain in the Nineteenth-Century Netherlands. MA Thesis, Leiden University, 2021.

Jörg, C.J.A, Campen, J., Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Amsterdam/London: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam/Philip Wilson Publishers Limited, 1997.

Kruijff, J.R. de, ‘Gemonteerd Porcelein’, De Amsterdammer, weekblad voor Nederland, 18-01-1880, 4.

Lorm, J.R. de, Amsterdams Goud en Zilver. Amsterdam/Zwolle: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam/Waanders Uitgevers, 2001 (2nd revised edition).

Lunsingh Scheurleer, D.F., Chinesisches und japanisches Porzellan in europäischen Fassungen, Braunschweig: Verlag Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1980.

Mars, ‘Porselein’, in De Navorscher, een middel tot gedachtenwisseling en letterkundig verkeer tusschen allen, die iets weten, iets te vragen hebben, of iets kunnen oplossen, 1860, pp. 136-140.

Schroder, T.B., Renaissance and Baroque Silver, Mounted Porcelain and Ruby Glass from the Zilkha Collection. London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2012.

Vreeken, H., Dekker, A. den, Goud en Zilver met Amsterdamse keuren: de verzameling van het Amsterdams Historisch Museum. Amsterdam/Zwolle: Amsterdams Historisch Museum/Waanders Uitgevers, 2003.

Wilson, G., Mounted Oriental Porcelain in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1999 (revised edition).