The Rijksmuseum as we know it today – the imposing building between the Stadhouderskade and the Museumplein in Amsterdam – has existed since 1885. Paintings, prints, drawings and objects were amassed in this new museum building from various locations. Porcelain could be found in the Nederlandsch Museum voor Geschiedenis en Kunst (Netherlands Museum of History and Art), a museum that as a whole moved from The Hague to Amsterdam, where it was incorporated into the museum building as an independent institution. In 1927 it was incorporated by the Rijksmuseum and became its Department of Sculpture and Applied Art.

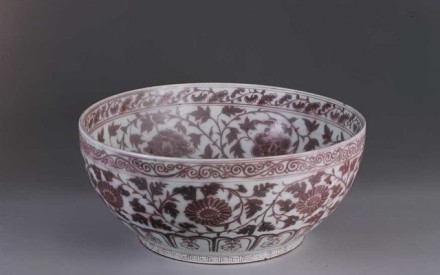

The Rijksmuseum has collected Asian ceramics in two ways: to represent historical living culture, and to illustrate the production of works of art from Asia. The Rijksmuseum’s collection of applied arts is extensive, renowned and diverse. It offers an impression of Dutch applied art in a European context. Since luxury goods imported from Asia played an important role in the Dutch interior, Chinese and Japanese porcelain was traditionally collected as well. This porcelain was also considered important because it had served as an example and source of inspiration for Dutch faience – the famous ceramics known as ‘Delft Blue’. The earliest museum pieces originate from the Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden (Royal Cabinet of Rarities), a nineteenth-century museum in The Hague. When it closed, most of its collection ended up in the Rijksmuseum. The porcelain from the Royal Cabinet of Rarities provided a good overview of the types of porcelain that wealthy families had in their homes in the Netherlands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In the twentieth century, curators acquired specific pieces in order to present a more diverse picture of Chinese and Japanese ceramic production, such as a covered pot from the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) (fig. 1) and an enamel-on-biscuit group of sculptures. The largest contributions to the collection resulted from donations, sometimes of large collections. The most important of these collections are those of J.C.J. Drucker (exhibited in the museum from 1923), J. Spoor (1936) and Robert May (1946). Although they reflect the taste of the times, they are rather conservative: they include a lot of porcelain from the Kangxi period (1661-1722), with a special emphasis on famille verte and powder-blue wares. The large collection of I.G.A.N. de Vries (1923) had a different emphasis: it was entirely devoted to European representations on porcelain (fig. 2).

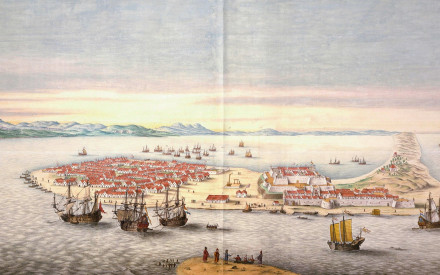

Despite the curators’ occasional acquisition of earlier and different kinds of objects, the Rijksmuseum’s ceramics collection still focused on porcelain brought to the Netherlands during the time of the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC). Internationally, interest in old Chinese ceramics had been growing steadily since around 1900. Western interest in Japanese ceramics that were appreciated in Japan itself, for example in the tea ceremony, began even earlier. Cooperation with the Koninklijke Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst (KVVAK, Royal Asian Art Society) ensured a better balance. The KVVAK began collecting Asian art shortly after its founding in 1918, especially objects that were highly regarded works of art in the countries where they were produced. Although the scope of the collection was much broader (sculptures, paintings, textiles), this also applied to ceramics: for example, tea ceramics from Japan, Song bowls and Tang-dynasty tomb figures (fig. 3) from China, and ceramics from Southeast Asia and Korea (fig. 4). From 1952 onwards, the collection was exhibited in the Rijksmuseum’s galleries (fig. 5). The Rijksmuseum has had its own Asian Art department since 1965, where acquisitions are made in the same spirit as the KVVAK. The KVVAK has loaned its collection to the Rijksmuseum, where it is exhibited.

The Asian Art department has managed both the Rijksmuseum and the KVVAK collections since 1990, a total of nearly 2,300 pieces of Chinese ceramics, roughly 600 Japanese ceramic objects and about 50 from other Asian countries.

You can visit the website of the Rijksmuseum by clicking here.

Literature

Christiaan Jörg, Chinese Ceramics in the Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; the Ming and Qing dynasties, Londen/Amsterdam 1997, pp. 11-23 (‘History of the Collection’).