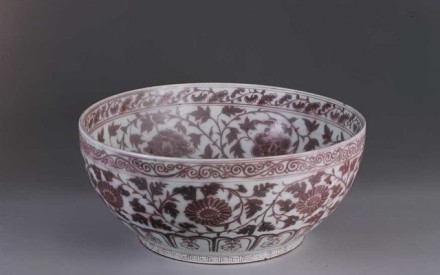

Travellers to the Netherlands in the seventeenth century were often surprised by the amount of Chinese porcelain they encountered in people’s homes among all strata of the population. It is indeed remarkable that not only the well-to-do but also people with a rather modest budget apparently enjoyed displaying porcelain on cupboards, mantelpieces and along the tops of panelling (fig. 1). The blue-and-white porcelain from China arrived at just the right time. Economic success in this period had brought prosperity to more people than ever before, and the tumultuous times (the war against Spain and the struggle for religious freedom) offered opportunities to ascend the social ladder. It was precisely these social climbers who had no problem flaunting their success and expressing it through the latest trend – a presentation of Chinese porcelain.

During the second half of the seventeenth century, people often displayed so much porcelain in one room that it could be called a ‘porcelain room’. The princely Orange family, Stadholders in The Netherlands, played an important role in the development of these rooms. In the 1630s, Amalia van Solms (1602-1675, fig. 2), wife of the Stadholder, displayed so much porcelain in her art chamber in the Oude Hof in The Hague that one could speak of a porcelain room. She also had three shelves installed in a gallery in the same palace upon which she presented her porcelain. However, the porcelain room must have developed organically in several locations. Inventories from the first quarter of the seventeenth century indicate that merchants sometimes had hundreds of pieces in their comptoir, their office. Efficiently arranging so much porcelain on shelves in a fairly small room results in a magnificent display: a precursor to the well-organised porcelain cabinet.

The end of the seventeenth century saw the development of the most famous piece of furniture for porcelain lovers: the porcelain cabinet, a large cabinet on legs with glass doors (fig. 3). Ridges ensured that plates could lean against the back wall with smaller bowls and vases in front of them. Architects such as Daniël Marot (1661-1752), who also worked for the Stadholder court, made designs for chimneys and walls with a large number of consoles that accommodated Chinese porcelain (fig. 4).

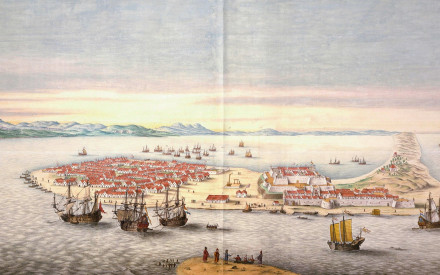

Imports of Chinese porcelain into Europe resumed at the end of the seventeenth century after the rulers of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) had established their hold over China, and production and trade flourished once more. This changed the status of the hitherto much coveted material. Until then, porcelain had hardly been used as regular tableware, at most as a bowl or dish to serve fruit and sweets. Now series of table plates were produced and used, as well as tea and coffee services. Tableware developed during the eighteenth century and the design and decoration of the various parts became uniform (fig. 5). These utility wares were usually stored away in closed cupboards. Interiors also became simpler and less crowded and the overfull porcelain displays gradually disappeared from view. The declining appreciation for Asian porcelain was also related to the development of porcelain in Europe, where Meissen had produced the first European porcelain in 1709 – soon followed by other factories. Until then, the manufacture of Chinese and Japanese porcelain had been both a mystery and a marvel for Europeans, but Asian ceramics lost its lustre with the European invention.

However, the porcelain was apparently not discarded but stored in attics, because when the appreciation for Chinese and Japanese porcelain was revived in Europe and the United States at the end of the nineteenth century, the Netherlands turned out to be the pre-eminent place to buy old pieces.

Literature

C. Willemijn Fock, ‘Frederik Hendrik and Amalia’s Apartments: Regal Display alongside the Triumph of Porcelain’, in: Peter van der Ploeg and Carola Vermeeren (eds.), Vorstelijk Verzameld; de kunstcollectie van Frederik Hendrik en Amalia (exh. cat. Mauritshuis), The Hague/Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 1997, pp. 76-86.

A.M.L.E. Erkelens, ‘Die Porzellansammlung der Amalia von Solms: Aufstellungsweise und Einfluss in Deutschland’, in: Siegfried Wollgast et al., Die Niederlande und Deutschland: Aspekte der Beziehungen zweier Länder im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Dessau: Kulturstiftung Dessau Wörlitz, 2000, pp. 108-115.

J. van Campen, ‘Chinese and Japanese Porcelain in the Interior’, in: Jan van Campen and Titus Eliëns (eds.), Chinese and Japanese Porcelain for the Dutch Golden Age, Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2014, pp. 191-212.

Teresa Canepa, Silk, Porcelain and Lacquer; China and Japan and their Trade with Western Europe and the New World, 1500-1644, London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2016.